I met Ramsés in person in 2023 when I visited New Orleans to give a talk on the evolution of popular Cuban dance music between 1959 and 1990 as part of the “Toda la familia” event sponsored by the organization Dile Que NOLA. He had come from Spain, where he currently resides, and was part of the event’s team of instructors. Nicole Goldin, one of the event coordinators whom I have already interviewed for this space, had the idea that Ramsés and I should stay in the same house. So, she arranged for it to be so.

Imagine that: two casino nerds sharing the same space for an entire weekend.

Since then, Ramsés has become like a kind of a brother from another mother to me.

When Ramsés told me that he and Dile Que NOLA had joined forces to sponsor the Cubason congress in New Orleans, I was overjoyed. Then he surprised me with something else: he wanted me to be part of the event’s artistic direction. Since then, I have been working with him and others to create a space that is a true oasis for social casino dancers. This interview, therefore, is not just a way to get to know Ramsés but also a way to understand why an event like Cubason is so, so necessary.

Some people call Ramsés “The Pharaoh of Casino,” but that doesn’t do him justice. The term “pharaoh” evokes something exotic and foreign to Cuban culture.

Don’t let the moniker confuse you. Ramsés is currently one of the most ardent defenders of the tradition of Cuban social dances outside the island.

DL: Tell me about how you started dancing casino.

RS: I started dancing casino at the age of 16. My mom, along with my stepfather (who is Spanish but dances good casino), tried to teach me when I was 12, but it didn’t work out. At 16, I had an Argentinian friend with whom I studied. His girlfriend, Sandra, had signed up for a Cuban salsa course with Gastón Carvallo.1 After three months, he told me she was left without a partner and wanted me to dance with her. Being Cuban, I thought to myself: how can I, being Cuban, not know how to dance casino when an Argentinian does?

So, I enrolled in my first Cuban salsa class with Gastón. I went dressed like a rapper, my fashion at the time: Ecko pants and t-shirts, hoodie, Timberlands. Anyway, my experience with casino comes about five years before Yoel Marrero [this will be discussed later]. And so, that was my first approach: through a Cuban teacher, but never through the word casino, but rather “Cuban salsa.”

In fact, one anecdote that I will never forget is that when I arrived in Spain at ten and a half years old, I was the only Cuban in school. My teacher asked me if I danced salsa. I responded: “I don’t dance salsa, but my mom dances casino.” My teacher and I never understood each other. She didn’t understand what casino was, nor did I understand what salsa was. So, when I approached a “Cuban salsa” class, I thought I was learning something similar to casino, but not casino. In fact, what I danced wasn’t what my mom danced. That’s why my approach to the Casino Para Todos Foundation was immediate because I saw the famous black and white video of Yoel at Villa Danza, dancing “like a woman” in high heels and pointing with a blue circle at technical aspects of the elbows, knees, steps, and turns. And saying things that Gastón never explained to me in classes. He dancing the way my mom danced. I made a direct connection. I said to myself: What I’m seeing is how my mom dances, but not how the people around me dance. What is that?

DL: So, as a Cuban of the diaspora trying to get closer to your culture, why was it important for you to approach casino? Why not baseball, for example?

RS: For two reasons: because I come from a family of well-known Cuban music musicians, starting with my grandfather, who was an orchestra drummer; my dad was also a drummer. My older brother played timbales for Bamboleo at 17. I was always directly connected to Cuban music and dance culture through my mom. My mom was Guarachera de Regla, a casino dancer, and always wanted me to dance. My mom also played the piano.

My relationship with Cuban art related to music and dance was always very direct. There was a part of me that wanted to show my mom that I could also learn to dance…and show the rest of my family that even if I didn’t dedicate myself to music per se, I could dedicate myself to another part of it, which in this case was the interpretation through dance.

This was perhaps even a little traumatic: wanting to prove that I was also Cuban, that I was connected.

DL: I understand that. Your family grew up in Cuba, your older brother too. However, you arrived in Spain at 10 years old. You were really brought up outside of Cuba, and that brings its own challenges.

RS: Exactly. As a child, I always accompanied my dad to rehearsals, to concerts. In fact, I didn’t become a musician because I rejected music. Imagine a six- or seven-year-old kid next to a drum set for three hours in a rehearsal. That was very hard for me. It made me anxious to go to rehearsals with my dad. But of course, I had a direct connection.

DL: Yes. There was no way not to do something with that.

Tell me then how you started to get closer to the casino that your mom danced.

RS: It was precisely through that video of YM that I mentioned. Then I started reading what he wrote and the online discussions he had. Those discussions, for me, being more scientifically inclined, always seemed more convincing, more logical compared to what was on the market at that time.

At that time, I was also attending dance congresses. One that marked me a lot was one of the Cubamemucho,2 where I met Adrián Valdivia. I didn’t even know what columbia was back then. At that congress, I approached a range of Cuban folkloric dances that I really liked and that opened up a new horizon within the dance scene for me. But although it interested me at that time, I didn’t delve deeply into these dances until I came across the Foundation, its goals, and what it wanted to achieve, how all of that was going to help Cuba and Cubans in general; how we could contribute to improving the market. That was the moment when I said to myself: I have studied what I have studied, but this interests me more. I want to research more about this; I want to professionalize myself more. In reality, the credit for my determination in this goes to YM and the objectives of the Foundation at that time. Also, when I got involved, I found people who were already familiar to me, like Eric Turro (whom I knew from YouTube), Adrián Valdivia, whom I had already met in person. They were familiar faces who shared my same interests.

DL: Tell me a bit about why you got involved in this Foundation. What was happening around you that made you identify with the Foundation’s goals? What did you see as a Cuban outside of Cuba that was happening with your culture abroad?

RS: When you want to associate with something, sometimes you look for a common enemy. And that common enemy at that time was on1/on2 salsa. It was what was trendy. So, that Foundation was the first organization, the first group of people, that openly talked about a series of things that were happening with Cuban culture within an already established market.

DL: What were you rejecting? The idea that there were other ways to dance or that salsa concepts were being incorporated into casino?3

RS: The latter. I even considered dancing on1 salsa at one point. There is nothing that says that, as a Cuban, I cannot dance another style. In fact, I went to Benidorm to attend one of the largest salsa congresses in Europe at that time. I paid my way to go and meet a Cuban, who was then the director of a group called Tropical Gem, one of the most well-known line salsa groups. I wanted to meet him in person (we had mutual contacts) and ask him, face to face, why he did this. I won’t recount the whole night’s conversation, but his answer, very succinctly put, was: money.

So, this didn’t resonate with me. I also saw that that this dance scene treated Cuban dances with disdain. Then I understood why: salsa was much more attractive than casino, which had the stereotype of a Cuban tangling you up with knots, the woman not being comfortable, with no artistic beauty. In fact, the Cubans who succeeded the most in the market were the ones who mixed those concepts, such as Seo Fernández or Maykel Fonts. So, you see all those Cubans approaching that market with a “Cubanized” style—so to speak—but you don’t see casino. We, the casino dancers, belonged to a lower society of sorts. The discrimination was real, even from Cubans who joined this aesthetic.

So, when the Foundation and the entire team began advocating in favor of Cuban social dance, I felt identified.

DL: That was literally my experience. I had the same trajectory as you. I tried to learn in Cuba. I asked my mom and one of my cousins to teach me, but nothing came of it. It was when I got to college that I started to learn more formally.

Also, at university, I was part of a group that danced the famous Miami style. There was another group that did on1 salsa. Our group wanted to do what the salsa group was doing. We wanted to incorporate concepts from that into what we were doing. There was always that inferiority; that idea that casino was just the rueda, that it was only for fun and having a good time. It wasn’t serious. There was no technique, nothing. It was simply to make friends.

On top of that, I went to salsa congresses, and they didn’t play music from any Cuban group—when in Cuba, we listen to dance music from all countries. Outside of Cuba, suddenly, I found myself completely isolated. My culture didn’t appear anywhere in a congress that was supposedly Latin American. On top of that, there were no casino workshops at salsa congresses.

I also remember going to a place that had an event on Thursdays called “Havana Nights” and they didn’t play anything from Cuba. It was just a name, buttressed on the stereotyped idea of Cuba from the 50s—and it didn’t even try to replicate that because there wasn’t even an atmosphere from that decade. They used the name to attract people, appealing to what “Cuba” means in the American imagination.4

So, I already had that trauma. And that’s where I found YM, a person who was rasing a metaphorical flag and creating a space for casino. What I’m getting at is: it makes sense that both of us reached the same conclusions and the same person because we had similar experiences. And that’s something that people who don’t know your story or mine often don’t consider. The Foundation wasn’t creating a problem, it was talking about a problem that already existed. By joining the Foundation, we were reacting to that problem.5

Well, since you wanted to connect to your identity through casino and approached the Foundation because it was promoting that connection with what was done in Cuba, how important, in your opinion, is it for a casino instructor who is not Cuban to be connected with Cuban culture, to be in community with Cubans? To teach casino, is it enough to have a super technical and precise knowledge of the dance?

RS: Obviously. Otherwise, we fall into cultural appropriation. I believe that this is necessary and almost mandatory. If we disconnect the Cuban from Cuban culture in the hands of a foreigner, we enter into a huge problem.

I’ll be honest with you. My focus wasn’t there originally, but thanks to the conversations we’ve had lately, I’ve tried to broaden my perspective because I’ve seen that, yes, it can be a problem. And it is problem currently. The thing is, there are so many problems that you end up focusing on what seems most immediate.

So, yes: it is mandatory that there be some kind of relationship with Cuba and with Cubans, just as you would expect with any other culture. I myself do this unconsciously because it’s so normal for me to have Cubans at my events. Since I was little, I always sought that validation. It doesn’t make sense to me, for example, to dance bachata without seeking validation from Dominicans. Since it was so normal for me, I didn’t see it as a problem. But now I’m seeing things beyond my perspective, and yes: I’m realizing there is a problem with this.

DL: If that is so important, what are the consequences of not being in community with Cubans?

RS: It’s the reason why we’re doing Cubason [more about Cubason later]: to fight against those events where everyone profits (because in the end, it’s a business), where there is a use of an external culture for one’s own benefit without any kind of morality, control, care, and credit (which is the most important thing). I think there has to be some influence from Cubans who are dedicated to this. After all, it belongs to the Cubans. At a minimum, Cubans should be represented and somehow receive compensation, whether participatory, with some kind of advantage, economic—one of those ways.

DL: I agree. In the end, it is inconceivable, in any other context, for this to happen. Can you think of something that has happened to you where you have seen the harmful effects of dissociating Cuban dance from its culture?

RS: Where I see this being much more visible is in highly developed countries, like the Nordic ones. The clearest example that comes to mind is Switzerland, because I know a bit about what happens there. Switzerland is the country where there is the most dancing in the world per square meter. It’s a pretty small country, but it’s where the most dancing happens. Yes, they dance everything, but there is a dominant market for the salsa dancing. For Cuban dance, it’s hard to find a Cuban teaching anywhere there. And if you do find a Cuban, it’s likely that they have a school with a Swiss partner where they do Cuban fantasy dances. That Cuban is a kind of mercenary. Just like the Swiss, this Cuban teaches everything and profits in every possible way. I see them twice a year when they come to Mallorca. These schools are money-making machines—they’re not schools, they’re businesses.

The largest school in Switzerland is called Salsa Rica. It’s a school that has four huge halls, and every three months, six new courses open up where each person pays $300 a month, and when you finish several courses (if I remember correctly), they give you the option to be the instructor for the next new course. It’s a succession of misuse and embezzlement of culture to detestable capitalist levels. If you told me that with all this they are dancing incredible casino, contributing, making trips to Cuba…but no. You enter the school, there’s a huge Cuban flag in the background, all the classes are of Cuban salsa…and there’s not a single Cuban there. No one says anything.

Another thing I’ve noticed there is that they use our culture as just another leisure activity. And I didn’t understand this until I got it. You tell a Swiss person: “Can we meet up on the night of July 26 to dance when I visit there?” The Swiss person looks at their calendar and says: “That day I have a tennis match at 11 a.m. Then at 1:30 p.m., I have rowing and at 3 p.m. I have a Cuban salsa session.” In other words, they categorize this as just another activity. They are not doing it from the approach that we have towards other cultures. For them, it is so normal to have capitalism at those levels with any kind of foreign product that for them a salsa class can be the same as a tennis match, a movie at the cinema. They put it on the same level. That’s where you realize that they don’t even care that I’m Cuban. For them (of course, this is not everybody) there is complete dissociation.

DL: I didn’t know that. From what you’re telling me, this could be an extreme of what’s already happening in other countries.

RS: And this isn’t talked about as a problem because when you bring it up, it’s the same story: you’re complaining. You’re a frustrated, unsuccessful guy who, if you were doing things right, wouldn’t be talking about this.

DL: And “doing things right” is literally sustaining the system that is creating these issues. I mean, when people blame you for not “doing things right,” what they are really saying is: “You’re not adjusting to the system we have created to consume your culture in the way that we see fit.”

RS: “You’re the problematic one.”

DL: Exactly. The problem, of course, is the system they’ve created. And when you refuse to fit in and decide to stand up and say: “My culture deserves respect,” then they label you as divisive.

RS: They nullify you because what you’re presenting doesn’t suit them.

DL: Exactly.

Throughout this conversation, this dilemma has emerged about what the market is portraying as “Cuban,” what we’ve seen, and how we’ve tried to approach the culture more authentically. And how the Foundation was an alternative to all this.That was almost 12 years ago. The Foundation, if I’m not mistaken, is still standing. But it’s led by a very toxic person who often sets us back with his racist, homophobic, sexist, Eurocentric rants.

So, if the initial response to what was happening with Cuban culture abroad was the Foundation, and now the Foundation is very problematic, what is the alternative?

RS: We need to be able to separate the work from the author. All its ideas, as ideas (perhaps some of them are too idealistic) are fantastic. We need to hold on to that and somehow create something parallel. In the end, we were drawn to that because of an affinity to these ideas.

The alternative then is Cubason. And here I will also separate the idea from the person. Cubason has to act as a variant to that. Whoever wants to go along with YM, go ahead. Unfortunately, I have to validate the good in the ideas, but I can neither validate nor recommend the person because, as hundreds of people know, it’s a deal with the devil.6

If in the end, you ask why we are all here, it all boils down to the fact that we all like dancing casino. Even if some people see Cubason as a union of “exiles” from the Foundation and everyone new who wants to participate in this and follow these goals that the Foundation had, the common denominator is that we like dancing casino.

DL: What other alternative is there for people who don’t want to associate with YM, but also don’t want to associate with people who were once associated with YM?

RS: We’re not the only ones. There are other groups interested in Cuban social dance who want a better relationship with Cuba and Cubans. There are nuances. I can’t deny you wanting to approach casino through someone other than me. Now, considering everything in the market, let’s say that what most resembles this kind of goal is what many of us (those who will be in Cubason) share. That’s why we want to come together in an event, which in turn is a concept.

Apart from this, I would recommend that the person go to Cuba and experience it directly with native Cubans who have no connection with foreigners or foreign products.

DL: It’s a bit ironic, isn’t it? “Go where the Cuban who hasn’t connected with foreigners…so they can connect with foreigners.”

RS: [Laughter]

DL: Precisely there is where the importance of being in community with Cubans comes in—and having it as a requirement if you are going to teach our dances or promote them in any public way. For me, it is very important that non-Cubans be very aware of the power dynamics that can exist when they interact with Cubans in Cuba. (And here I’m reminded of what was often said in the U.S. when Obama renewed relations with Cuba: “I have to go to Cuba before Americans ruin everything.”)

That’s why the work that has to be done from the outside is so important. We don’t want people to continue recycling power dynamics that “ruin everything.”

RS: That’s why the task of raising awareness for me is the only tool we have to make this work. We are destitute in all aspects—legal, economic. The only thing we have is the power to raise awareness—and for people to want to be aware. That’s what drives me.

DL: In the end, all of this is an ethical matter. And that’s what many people don’t see because they see it as a business. But it’s an ethical issue. It has to be. We are talking about a culture that represents a people. It must be represented with dignity.

And speaking of this topic, what has been the hardest thing for you in trying to promote casino in the way you do?

RS: People, for personal interests, don’t want to recognize the existence of a methodological system. It’s a constant battle, and it’s complicated. When you say you have a methodological system, people think that a methodological system is the way you do things, and that everyone has their own particular way. People don’t understand that a way of doing things is not a system. So, the hardest part of what I do is that I’m competing in a market that is not regulated, and since it’s not regulated, you get a lot of criticism when you say things should be one way and not another. Obviously, I’m not competing in a market full of Cubans where everyone is doing empirical dance and each one is explaining the Dile que no in a different way. We’re talking about what prevails is precisely the back-step, a casino that looks like salsa at times, which is very static—in other words, very serious mistakes.

You’re in a market where there is quite disloyal competition—if we have to call it something—and what you present is an alternative that interests few. Because among them there are no such discussions. Back to the same: you’re the villain when you try to sell a product that better reflects the reality of Cuban dance. That, even within Cubans themselves, is not convenient due to interests. That is the biggest difficulty I still face.

I changed my way of seeing this: I’m not going to convince everyone, but I will offer, with clear results, this product in the market, and whoever wants to buy it, they can. Who buys it? The ones who really have a more curious interest, the ones who resonate better with what I explain, the ones who see the results in the people I train, the ones who have a slightly more critical analysis. My message is very different: I’m going to teach you how Cubans dance…so you can dance with Cubans. In fact, Cubans who have danced with my students have given me very positive feedback on my work. That’s a source of pride for me.

DL: How do you try to approach Cuban culture in your classes, beyond the technique? Is there space in your classes for that?

RS: I show my students many examples, like videos of “Para bailar casino” that illustrate the figure we’re learning. I always look for external, graphic confirmation—from Cubans inside or outside Cuba, people who have understood this and are dancing like them—and send it right away.

Also, parallel to this, I personally saw the need to become a promoter. I sell a product. If there’s no market where you can consume it, we’re doing nothing. And that, believe it or not, is more common than it seems: people who want to shirk the responsibility of creating a space for that.

I live in Mallorca, a very small island, and I put so much pressure here that practically—if I had to say it in an “egotistical” way—I have killed salsa dancing here. My pressure with casino is so great that I have completely overshadowed that market. Here, every week, we have an event where you can dance to Cuban music. It’s a cycle that needs to be maintained, and we must always try to include Cuban figures, even people who don’t do things so well, but always have that Cuban presence here.

DL: What do you mean when you mention Cubans who don’t do things “so well”?

RS: Cubans who are the antithesis of what I do, who are doing Cuban salsa, timba, etc.7 I’m very inclusive. That’s why I created a Cuban dance space where I invite everyone. What I do try to do is be mindful of the message. For example, two weeks ago, we had our monthly Cuban event. I invited a Cuban dancer who is very good at what he does. I put in the event description “Timba workshop (Cuban freestyle steps potpourri).” I always try to make things clear, but I have to be inclusive. In the end, this helps when building relationships and not falling into the “Yoelean” phenomenon, where only my way is good, and everything else is bad.

DL: Well, this also can create a positive feedback loop, in the sense that the Cuban who, through his experience, has been forced (or chosen) to do things that sell more but don’t respect Cuban culture, can see spaces like yours and say: “This can be done. I don’t need to teach timba [a dance that doesn’t exist in Cuba] when this person is teaching casino, and look how it works for him.”

For me, what many Cubans are doing is surviving within a market that has left them on the periphery. We have to consider the fact that many are recent immigrants. They are not like you, who came to Spain at 10 and had all this time to grow up in that country. These are people who arrive later and have to find a way to make a living as best they can. They need to eat.

That’s a nuance I’d like people to consider too. Consumers of this product, through their capital, can contribute so that Cubans don’t feel like they have to change things or do something they know isn’t done in Cuba. (All Cubans who do “timba” know that’s not how casino is danced in Cuba.)

Things like “timba dancing” are artistic, individual interpretations that they sell using, as a basis, the stereotypes of Cubans. They’re selling an idiosyncrasy as something more global. That is to say: “This way I interpret the music is how it’s danced in Cuba.” And since the person consuming this isn’t informed either and only knows the stereotypes (because they’re not connected with the Cuban community, because they don’t have Cuban friends who dance casino), they don’t realize these are individual, artistic interpretations and not representations of how it’s danced in Cuba. That’s the other side of the coin that I like to emphasize a lot: the role an informed person can play when consuming Cuban culture.

RS: The majority—if not the only ones—who dare to teach Cuban dances to a foreign audience are professional dancers (bailarines). The bailarín goes out and says: “What can I do with what I know?” They realize that most cities don’t have dance groups or companies doing shows where they can substitute doing what they do. So, they look at what’s on the market, what everyone is teaching: salsa. So they start teaching that because, as dancers, they can create the idea that they can do it. They realize that in Cuba they’ve never done that. An empirical dancer never comes to that conclusion and starts doing that. So, among ourselves, there’s that dilemma because, unfortunately, you find an intrusion of a person who, out of necessity, enters a market they don’t know, starts doing what they’ve always done (which is not how it’s danced socially in Cuba).

All this creates a paradox: the Cuban themselves, because they don’t know how to do social dances (because that’s not what they studied) start to invent and validate something that doesn’t really exist there (though they sell it as “Cuban”) and the snowball effect turns into an avalanche.

DL: With that, I want to go back to the lack of connection with the Cuban community. When you go to pages that do promote casino, you see ordinary Cubans (not dancers) who go to those pages and start criticizing exactly what you describe. And they say: “This is casino; not the nonsense I see being done.” It has become so normalized as “Cuban” what you just described, and ironically the Cuban doesn’t identify with it.8

But you have to be in community with Cubans to know this and create spaces that represent Cubans. Look at the pages of Dile Que NOLA or DC Casineros. Many Cubans leave comments precisely because they feel identified with what they’re seeing in those spaces.

The videos of these artists you mention, generally, don’t have many comments from Cubans. Yes: there’s the occasional Cuban (who doesn’t know how to dance and therefore doesn’t know what they’re seeing) who says: “Oh, look how nice.” But usually, foreigners are the ones commenting on those videos.

RS: We’re talking about a product made by people. When there’s this human factor, interpersonal relationships come into play, with emotional issues, and in the end, you realize that there might be a Cuban commenting in favor of that because they’re friends, or because they felt identified with the song. They see their culture represented in some way.

But the one who knows how to identify Cuban social dance and sees that, doesn’t go by interpersonal relationships. They’re the ones who say: “Hey, that doesn’t look Cuban.”

It’s a delicate subject. Cubans themselves tell you that’s not Cuban, but then there are other Cubans, who because of their relationships with these artists, validate what they’re doing.

DL: Here comes the importance—and that’s why it’s so important for me to have it—of a theoretical framework. In any discussion, there will always be different opinions. But for example, if I know, because I’ve studied, that feminism is valid because it does all these things to empower women and create a more equitable society, and suddenly a woman comes and tells me: “A woman’s place is in the kitchen. It always has been and always will be,” that neither invalidates feminism nor makes invisible the systemic problems that feminism seeks to address—unless you, through a lack of knowledge of the power structures that exist in our society, invalidate and make it invisible.

Another very current example: a person who says: “Look at this Chinese guy,” but doesn’t know if that person is from China. They’re speaking from a racist stereotype. Another person, knowing that this is a stereotype that has caused a lot of harm, doesn’t say “the Chinese guy,” but “the Asian.” The first person, maybe without realizing it (maybe they are racist), is making a racist statement; the other, who has studied this, understands the systemic problem and why calling any Asian “Chinese” is so problematic.

These conversations need to be had. So, let’s study things as they are and have a theoretical framework to say: “This may look very nice [within a European and neocolonial aesthetic worldview], but look what it’s doing to Cuban culture [precisely because it’s framed within a European and neocolonial aesthetic worldview].”

RS: Yes. We are in that initial phase now, where we are precisely presenting a sociocultural theoretical framework (raising awareness) that did not exist until now.

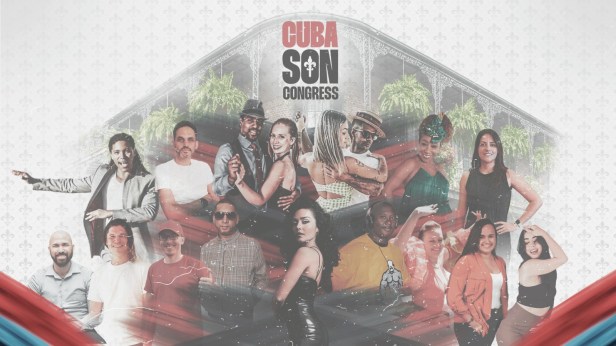

DL: Well, let’s talk about Cubason, that dance congress for the casino dancer that will take place from August 8-11 in New Orleans, and that you are organizing with the help of Dile Que NOLA.

RS: Cubason is the result of the many attempts I made from the time I joined the Foundation to create spaces here in Europe to combat everything we’ve talked about. I proposed it to YM for many years, but he never wanted to do it. It was in 2019 (the year before I had left the Foundation) that I decided to hold a gathering. Originally, it was called “The Meeting.” The description was: “The meeting of dancers who love Cuban music and social dances.”

I called colleagues who shared this vision with me and who had been looking for something like this for a long time. We shared that first installment of the event in Mallorca. The idea was to have better quality in the workshops, in the tools that people would take with them; to have live traditional Cuban music.

It was also important that we got to know each other. We are teaching a product that, if we are the only ones selling it, people will wonder where else they can go to dance like this, and if you don’t give them an alternative, they will go to a Cuban salsa event. And then you’re screwed because, in the end, alliances and friendships make people forget that this is also a cultural matter. I had to create Cubason so that everyone could see how many people there are in the world doing this.

Cubason brings to the market a space for people who share our ideas; who want to go to an event to learn and meet people who teach in a way that is closer to the social Cuban dance seen in Cuba. Cubason is also a space where the starting point is culture, and delves into what we need to preserve casino—and not from the economic side. By producing this type of event, we ensure that we don’t end up needing someone like Maykel Fonts selling us the event. As Cubans, we empower ourselves in this way.

Another thing: when I realized that this could become a concept and that people were looking for this left and right, I distanced myself from the concept of Cubason. Now I am simply “the connector”—so to speak. That’s why I don’t like to say that Cubason is mine. I’m just another person involved. What happens is that I pull the cart for everyone. And what I carry in the cart is yours, mine, and everyone’s who wants to contribute to the growth of the Cubason concept.

DL: Both Julio Montero and Nicole Goldin have told me that what they appreciate about Cubason is that it is a space for the dancer. Tell me a bit about that.

RS: Everyone who attends festivals (Cuban or not) at some point realizes that these spaces have become places where those who aspire to more (e.g., to become professional dancers at 40) are in community with others who have the same aspirations, and it creates a buzz where the euphoria is so great that this is what prevails at these events. We forget that in the end, what we are doing is dancing casino; that there are people who just want to share with other dancers, dance the same Cuban language, and learn how to dance more authentically. What ends up happening is that the excitement and euphoria of many festivals lead to the creation of adulterated sub-products sold as Cuban (i.e., “timba with guaguancó workshop,” “casino with afro”), which only serve to put on a show… that you will never perform.

Cubason is an event for social dancers. For the dancer who just wants to enjoy the dance itself (not the visibility they might have), there are no events like this on the market. And yes: at salsa socials everywhere you can find casineros, but they are like us: they go to those events because there is no other alternative.

DL: You talked about “adulterated sub-products.” I want to clarify that, not to talk about the dance of “timba” or anything like that, but because it is true that most of the people who go to teach casino at Cubason have gone through the MCC to learn casino, which is the creation of YM. Personally, I have seen that if you are not careful, the pure focus on technique can create a dancer so focused on the technique itself that they end up completely disconnected from Cuban culture. They can even tell you (as they have told me): “In Cuba, people don’t know how to teach casino.” This confused me a lot because, for decades, casino has been perfectly transmitted empirically within Cuba.

RS: A confession: I have been one of those who said this. Previously, I myself spread that idea.

DL: And that is precisely the problem that can arise from working with the MCC (Método del Cuadro del Casino) without cultural awareness: it can create a false idea of what authentic casino is, precisely because many see it as a totalitarian method and not as a way to approach Cuban culture. It can be, in fact, a way to distance oneself from the culture.

Given all this preamble, how do we ensure that Cubason is not creating an “adulterated sub-product” of Cuban culture through MCC?

RS: First, we have to understand that the MCC is nothing more than a set of tools that take you from point A to B in the shortest possible way with most of the problems that occur in dance already solved. But it is just that: a set of tools. What happens is that we should never deny something that, as a tool, improves pedagogy. That would be to fall into the opposite, like someone who, after having danced for 20 years, says they don’t need anything.

Be it MCC, CCC, or MMM in the future, anything that can improve and describe the real phenomenon, we should use it. If we contextualize it within the teaching market, we are obliged to approach it. This perspective is more common among those on the scientific side than those on the artistic side, who focus more on their experiences. The MCC brings you closer to casino through a set of technical tools. The final phenomenon—casino—can contain that, but also not. MCC does not encompass individualities that occur in dance spontaneously. It is a product that responds to a culture, and that culture changes. You can arrive with a toolbox to try to dance, but in doing so, you encounter more things. The toolbox is not the end. What this toolbox does give you is an understanding of the phenomenon. This is what people need to understand: until then, no one could explain the phenomenon. There is an approach to the structure of the dance that is necessary to know; beyond that, there are many more things: stylistic, musical concepts—things that also make up casino.

MCC is not the end; it is a tool that helps you understand the structure of the dance and the technique. And as a social dance instructor (not as a social dancer, the social dancer does not require this), it is your duty (moral, professional, ethical) to have as many tools as possible that describe the real phenomenon of dance, as accurately as possible. Obviously: you will never get completely close because the reality of dance is subject to the individual experiences of each dancer.

DL: How does Cubason ensure that it provides that toolbox, yes, but also provides sufficient cultural context? Because if all we do is give the toolbox, we are doing the same as other events where they put a giant Cuban flag in the background and that’s it: that’s culture.

RS: First of all, at Cubason we do not give space to products that do not belong to Cuban culture in any way. We do not create workshops for things that do not exist in Cuba. Now: we do give space to workshops like the women’s styling workshop, but we always try to address those points that the tool does not give you. Secondly, by creating specific workshops for different genres of Cuban social dance: son, danzón, son montuno. Workshops where we talk about other aspects that are important for the dancer, such as musicality, which are linked to Cuban culture and the history of Cuban music (even though this is not talked about much in Cuba). Thirdly, each class tries to contextualize what it teaches so that when people go to Cuba, they do so with a better idea of the cultural and social context. You leave Cubason knowing that what you are doing is part of a culture, which occurs due to specific circumstances (for example, the workshop we are going to do on conga santiaguera). Fourthly: we are calling on Cubans. It is necessary for Cubans themselves to validate the content and the experience of the event. This makes Cubason different from what is out there.

DL: How does Cubason encourage attendees to be in community with Cubans?

RS: One of the things we are going to do is panels. In them, we are going to expose conversations of this type, where we invite and encourage people to become aware of what is currently happening in the market, the good and the bad that is happening, how the leaders of Cuban dance groups can return to their communities and implement a new discourse and a new way of approaching Cuban culture through their academies. For me, it is the most immediate and necessary thing. People know that in the workshops they will learn about dance, but about culture, you learn by talking about culture; creating spaces where we talk, help each other, and generate strategies on how to approach Cuban culture more ethically.

The idea is that these things help people who are leading their communities and are unconsciously falling into these errors of cultural misappropriation and appropriation. I always start from the premise that this is done unconsciously.

DL: Yes. The harmful thing about these problems is that the systemic issues are invisible.

RS: The issue is that these problems have been raised by a very toxic person in incorrect ways. Now we will have a space where there are Cubans (plural), who have no connection to this man, who will talk about these problems. Now, there may be disagreements. What we want to do is expose the problem and strategies to solve it. We do not want to point fingers; we are not going to cut heads at the event.

DL: Of course. And in fact, you and I don’t agree on everything. Even when people are strongly connected to a goal, there are discrepancies. And that’s fine. That’s what I want people to see: there are different ways to think about the same thing, as long as we are all pulling the same cart.

For me, as someone also helping to organize the event, the most important thing is how empowered the Cuban is here. You say you are not the leader, but it is your idea. That matters. Your positionality as a Cuban has allowed you to see and experience things firsthand that wouldn’t have the same effect if they happened to someone else. And you have made decisions, therefore, that reflect that experience that another person, again, although they might experience the same thing, it doesn’t affect them in the same way because it’s not their identity, it’s not their culture.

RS: The line of events that led me to this is: as a Cuban, I felt identified with my organic product (the casino dance); when I entered the market to do it, I found that I was the only one doing things authentically; I found that there was no market where we, as dancers, could consume it; so I had to become a promoter, create a local space to do it; at the same time, this required internationalizing the idea so that other communities could see that it is possible to authentically bring the product to people, always approaching Cuban culture.

All this—the problems and the idea—can be reflected in a space like Cubason. Cubason is born from the experience of a Cuban, inserted in the market, frustrated by his experience within it, and needing to raise awareness. Many of us see ourselves reflected in that idea, and that’s why we go to Cubason.

DL: And here also comes this idea I was talking about power dynamics. Those who go to Cubason are not there to consume their idea of Cuban dance. Instead, they go to Cubason to hear us Cubans say: “This is Cuban, this is mine. Here I am in charge because this is my culture.” And that is very important.

Clearly, this will make many people uncomfortable because silence from Cubans has been so normalized that it’s the non-Cuban who comes to impose what Cuban culture should be. It’s the foreigners who have historically been empowered in this context: they are the ones who go to Cuba with capital, they are the ones who hire Cubans in Cuba and tell them what they want the Cubans to teach them; they are the ones who sponsor most of the congresses in Cuba (the congresses in Europe, too, are mostly not made by Cubans).

A power dynamic has been normalized where the non-Cuban is completely empowered, and the non-Cuban’s comfort takes precedence over how a Cuban might feel.

At Cubason, what we are saying is: “Now we are going to talk. This is our culture. And if it makes you uncomfortable, that’s okay. Embrace that discomfort. If you are not Cuban, that is part of the growth you have to do as a person if you really want to be in community with us and promote our dances.”

That space, where that dynamic exists, does not exist outside of Cubason—at least as far as I know.

RS: Cubason is the response to what is happening in the market. Otherwise, Cubason would not exist.

DL: Correct.

Now, Cubason is not only an example of what a space for the casino dancer looks like when created by a Cuban; it is also a great example of how people who are not Cuban can ally with Cubans to create these spaces. Tell me a bit about what it has meant for you to be able to work with Dile Que NOLA to organize Cubason in New Orleans this August 8th.

RS: Due to the lack of human capital to do this, I have always had to observe who are the most reliable representatives of Cuban culture, beyond being Cuban or not. So, communities like Dile Que NOLA, as well as DC Casineros, give me hope that this is not a lost cause, that it is not a matter of Cubans against the world.

Alliances can be formed with non-Cuban people who, due to a higher level of awareness than the rest, are capable of understanding that this is a problem, that we must contribute to stop this from continuing, helping in different ways. In the case of Dile Que NOLA, they are a non-profit organization that is not governed by a market. Allies like them are almost indispensable at times like this. If we talk about the U.S. market, today no two communities contribute more to this mission than Dile Que NOLA and DC Casineros. It is important that we partner with them and that they teach us and help us in this process because they are doing it with a tremendous level of success, visibility, and ethics.

DL: To conclude, what is the hardest part and the most rewarding part of organizing an event like Cubason?

RS: Look, this has cost me to lose hair. In the first event, I lost part of my beard. Doing something like this is very stressful because you are making an economic product, but with a different background. You are going against the tide.

Beyond the workshops and parties, there is a very different goal and purpose. I always tell people: I don’t care if this makes me money; what I care about is that this is seen and exists because it is necessary. If we completely dissociate from this, in twenty years we will lose Cuban social dance outside of Cuba because there will be no place where it is generated.

All this is done out of love for the culture, not for economic reasons. There is nothing more beautiful than drowning in this economic process to finally emerge again and be able to give voice to these problems we talk about and try to create solutions and strategies.

Solutions and strategies that empower and return the culture to Cubans.

That is where the value of Cubason lies.

Notes

- To understand why Ramsés says he started with “Cuban salsa” and not casino, it’s important to grasp the difference. I have written about this in depth in this article. ↩︎

- The Cubamemucho congresses were where Cuban artists truly achieved international fame. After the success of the show “Para bailar casino,” many Cubans who participated there, such as Yanek Revilla, Diana Rodríguez, and Roynet Pérez, ended up teaching at Cubamemucho as well. This congress was instrumental in promoting Cuban dance culture in Europe. ↩︎

- Casino is not a style of salsa dancing. For an article that explains this in more detail, click here. ↩︎

- For more on the perception of Cuba by the U.S., click here. ↩︎

- Setting aside positive aspects, over time, the Foundation began to face serious issues, largely caused by YM, which contributed to my distancing from it, as Ramsés did at one point. For more on this, click here. ↩︎

- See Note #5 ↩︎

- Regarding the differences between Cuban salsa and casino, see note #1. For the supposed dance of “timba,” click here. ↩︎

- To see concrete examples and a to read a more in-depth description of this phenomenon, click here. ↩︎

ABOUT RAMSÉS SARIOL

Ramsés Sariol was born and raised in Cuba and now resides in Mallorca, Spain. He has over 10 years of experience teaching Casino and Son Cubano around the world, primarily in Europe. He visits communities that preserve the original traditions of Cuban dance. His workshops are renowned for being highly technical and deep learning experiences.

This is a really interesting and well written article. After reading this I have a much greater understanding of what the upcoming Cubason event is all about and I am excited to attend. Thank you for continuing to write these articles and for sharing your strong opinions despite the controversy they often generate. And — thank you for answering my question during the recent panel discussion in Baltimore. I appreciated the mindfulness behind your reply. See you in NOLA and please save me another dance!

Thanks for reading, and the feedback! Generating controversy is a good thing, specially when NOT doing it can lead to cultural appropriation. This can be crucial for raising awareness about important issues that might otherwise be overlooked. ontroversy forces individuals to think critically about their own beliefs and the beliefs of others. It challenges people to defend their viewpoints with evidence and reason, leading to a more informed and thoughtful discourse. Furthermore, by bringing controversial issues to the forefront, we can inspire action and promote social or cultural change. Controversy can be a catalyst for progress by highlighting injustices or pushing for new ideas and solutions.