Writing a blog like this is a solitary job. I don’t say this because the act of writing is, in itself, solitary; rather, it’s because there are no other spaces like this: a blog by a Cuban who is going against the current of a market that has cared little about how Cuban culture is consumed; who is saying that this cannot be dance for dance’s sake alone, but there must also be a cultural focus, a connection with Cuba and Cubans.1

For a long time, the ideas presented here have been very useful for many people, as they have told me, precisely because few are talking about these aspects of Cuban dances in the way I do. On the other hand, since there are few who speak, and one of the voices that has gone viral in this conversation is that of a certain extremely toxic individual (if you know, you know), some tend to associate me with his rhetoric, no matter how much I try to make people see me differently. If no one else says these things, the association is, unfortunately, logical.2

Julio Montero changes all this.

Julio Montero learned to dance casino in Santiago de Cuba, where he comes from, by imitating what he saw his friends doing. In short, he became a casino dancer the way most Cubans in Cuba do: empirically. Julio did not learn casino through any method. Julio is not and never was part of any foundation. Julio cannot be associated with anyone but himself. Today, Julio has under his belt a record of more than twenty years teaching casino in Vancouver, Canada, creating spaces for cultural exchanges in Cuba, and making visible the dance of casino, as is danced there, and this can be clearly seen on his YouTube page. He is also one of the few casino instructors who can say he has been a key part of a music video by one of the most recognized Cuban popular dance music groups, Elio Revé y Su Charangón, with whom Julio collaborated on the production of the video for the song “Cuba baila casino.”

Because of all his experiences, Julio represents an invaluable Cuban voice joining the conversation about what is happening with our culture outside the island (something I tried to highlight in this article), as well as how non-Cuban people can more ethically approach our culture (which will be a significant part of the dialogue below).

Without further ado, here is the transcript of the conversation I had with Julio Montero on the morning of June 21, 2024.

DL: Tell me a little about your experience with casino dancing in Cuba. What were your first experiences? What drove you to want to learn it?

JM: I had the fortune to learn to dance Casino at la beca.3 I studied at the Antonio Maceo Vocational School in Santiago de Cuba, where I entered at the age of 15, preparing with the intention of eventually studying medicine. Before entering that school, I imagined it would be a place of know-it-alls where almost everyone wore glasses, devouring books daily… Nothing like that. We studied a lot, but we danced even more!

Soon I learned two things: 1) casino at la beca is serious business. 2) If you didn’t dance casino, you weren’t cool. So I learned, and I almost became addicted.

My friend Frank was the one who taught me. We practiced all the time and everywhere. My classmates Iris, Tamara, and Liudmila also helped me. The 10-minute breaks between classes were used for practice. We also practiced at night after studying and in the dormitory. There, we helped each other among the boys to improve the moves because at the Wednesday night dance (called Recreación), we had to be sharp. Recreación was the big moment to dance, get into ruedas, and showcase one’s progress as a casino dancer. I reiterate: casino was serious business. I would mentally learn a sequence in advance so that when dancing at the recreación, everything flowed well.

DL: In other words, you learned casino empirically, like most Cubans in Cuba do.

JM: Of course, in my time there were no casino schools. Now, as a result of tourism and the commercialization of the dance, some schools have emerged, most of which I do not recommend. Good casino is learned among Cubans or at least with Cubans not infected by the toxicity of tourism and the distortions it has imprinted on the dance.

Look, there’s something in the process of learning a dance empirically that even I haven’t been able to decipher. I can only share my impressions on the matter—without any science to support me. Empiricism (learning based on experience) is a fascinating phenomenon because I learned to dance casino in a week. It all starts when you say, “I want to learn this,” and a friend responds, “Alright, here is how it is.”

The expression we use is aprender a marcar. What is that? Doing the famous Guapea. And there’s always a friend who says, “I’ll teach you aprender a marcar.” That’s the classic word used when someone says they know how to dance casino, at least at the most basic level.

Well, my friend Frank, who taught me, was already a seasoned casino dancer because his brother had entered the vocational school before him. His brother was in eleventh grade, so he had already gone through all that and prepared his brother before his entry to the vocational school. There were a lot of kids who already knew how to dance casino before arriving at the vocational school, like my friend Fausto. This indicates to me that Cubans also learn in other environments before entering such an exclusive one like a boarding school. I had seen this in secondary school too. At the little parties we had, there was already one or another who knew how to dance casino.4

I never put much thought into how all that was done. When I was in secondary school, my interest in dance was different. I started dancing in 1989, when the duo Milli Vanilli came out, along with the rap craze.5 It was a historical moment where a lot of things were happening musically. Lambada was playing, and there was already the “disco” dance done to Madonna’s music and breakdancing. It’s really impressive the number of rhythms we danced (or rather, used to dance) as Cubans growing up. I will confess that I first danced merengue before dancing casino. When I started with casino in 1991, in Santiago we danced everything: Jamaican dancehall with Beenie Man, Panamanian dembow with El General, merengue, punta, and we did the “running man” from rap inspired by Bobby Brown and MC Hammer, besides dancing European “disco” music avidly.

An anecdote about that: in eighth grade, I challenged a kid to see who danced the pigüe (running man of rap) better. After we had our duel, Liván—who I meet every time I go to Havana—came in and said, “Now I challenge everyone here to see who dances NG la Banda better.” When the NG la Banda craze hit (the word “timba” wasn’t even used), there were some steps that people did when dancing at concerts where there wasn’t room to dance casino because of how crowded it was. People did some loose, well-stylized steps and body movements. What Liván did impressed me with its humor but also its Cuban essence. And indeed, he threw some masterful NG la Banda steps. I took serious note and even learned them.

In short, returning to empiricism, by eighth and ninth grade, some driving forces had already developed during secondary school. So when I entered the vocational school, despite not knowing how to dance Casino, I already had rhythm, and that was the result of empiricism, as I never went to any dance school or took dance classes ever, just like the vast majority of us Cuban dancers.

DL: You already had your tumbao.6

JM: Exactly. And I think one learns casino so quickly for three reasons. The first is the visual learning that comes naturally from just growing up in Cuba. The second is being young, which makes things easier to acquire. The third is that casino is a dance performed while walking. That, combined with unorthodox teaching methods, yields quick results—methods that I couldn’t use here in Canada to teach a class.

DL: I really relate to that. When I started dancing in the late ’90s, I socialized at parties, secondary school social clubs, or at the disco fiñe (discos for teens) I went to every Thursday since sixth grade. In my time, a lot of techno was played. You’d go to the disco fiñe to do the Clock on the floor, breakdancing. And suddenly, they’d play a ballad like “Te quise olvidar” by MDO, and next thing you know, you’re trying to dance with a girl.

JM: Yes. And depending on how they held you by the shoulders, you’d get closer to her or keep your distance.

DL: Exactly.

JM: Well, getting back to casino: casino dancing became an obsession for me when I got to vocational school. One of the things I just told my students yesterday was about the rivalries. Since the vocational school was a huge school subdivided into several schools called “units,” when each unit held its gala, each one brought its rueda de casino. So there we were, sitting in the front row, watching what moves they were doing, making sure they hadn’t stolen any of our moves, and recording everything visually so that when it was our gala, we could perform a better rueda than theirs.

I remember doing my first rueda de casino in eleventh grade. The school’s assistant principal, noticing that we were the dance addicts, forced us to do a casino rueda show at the gala, threatening to accuse us of “ideological deviation” if we didn’t. My friend Fausto, a great casino dancer, directed it. The vocational school years were when I probably danced casino the most in my life.

DL: Tell me a little about that: the vocational school. In my case, just like you, before pre-university, I just danced socially, did my steps, but I didn’t dance casino. They’d play Charanga Habanera, and I’d do a basic Guapea. That was it. But I knew that when I got to vocational school, I would learn casino because that was the quintessential place for casino dancers. All the people who danced good casino in my town did so because they went to vocational school.

Why do you think vocational school (and not an earlier or even later space, like university) works so well for learning casino?

JM: Simply because of the boarding school life. We’re all confined to the same space where options are limited. In vocational school, you only study. Beyond studying (which consumes a lot of your time), the only other options for having a social life are sports and dancing. Dancing is one of the main activities in vocational school. In the city’s social life, there are many more options, distractions. Not in vocational school. This is all there is.

DL: You’re telling me that vocational school sharpened your tools for dancing casino. Logically, if you go through vocational school, you’ll be a better casino dancer because you had more practice. In your experience in Cuba, did you notice that people who went to vocational school danced better casino than those who didn’t?

JM: There are very good casino dancers who didn’t go to vocational school. But what vocational school does is that at least everyone learns to dance in a very similar way. The patterns of casino are faithfully replicated. Obviously, I would have to do a survey to ask which of the most notable (good) casino dancers today came from vocational schools.

What happens is that a vocational school student goes to university, graduates in engineering or whatever, and ends up taking another path in life. That’s why in the international casino scene, vocational school graduates are not very common. Many people who teach casino don’t come from that background. In fact, those who are not Cuban, on top of that, learn it outside the country… and what happens happens.

But I would say yes; the best casino dancers come from vocational schools. And when I say “the best,” I don’t mean from a stardom point of view, but rather those who dance well, who dance casino with the codes of a casino dancer, with the body language of a casino dancer; people who are distinctly casino dancers. Vocational school produces that, and in large numbers.

DL: You just told me that vocational school people replicated casino better with the “codes of the casino dancer.” What are those codes?

JM: Yes. Let’s go back to the context of confinement: there isn’t much diversity in terms of techniques for executing moves, although there was diversity regarding personal idiosincracies. What you do is copy what the friend teaching you is doing. That’s why the ruedas were quite uniform. That said, I still remember the way my different friend moved, so I insist on the personal differences, which become very evident when the casino dancer doing their basic steps. I remember how Tatiana Rodríguez and Sirlinda did their basic. She is the wife of a famous Cuban reggaeton artist, “El médico del rap” (from Candyman’s era). I also remember how my friend Frank did his basic step. There was diversity in that but all within a generally similar way of dancing casino.

Now, about the codes of casino. Talking verbally about the dance is difficult. The easiest thing would be to do a demonstration to illustrate what I identify as “codes,” but I can summarize them as follows: I recognize a casino dancer by their gestures and steps. There are body movements that are typical of a casino dancer. There’s a way of swinging the arms when doing your basic step. There’s a way of entering the Dile que no. Obviously, when a person dances casino stepping forward on the one, that already establishes another essential code. Even when doing the steps in casino figures, there are subtleties of the casino dancer that can be used to embellish the dance. For example, you can see how women, when entering the Dile que no, sometimes do a little dip. Or you can do it yourself when doing the Ola figure, for example.

There are also ways of doing certain figures. I’ll give you an example: the Dile que no, almost everyone outside of Cuba does it, in the lead role, by taking a step forward on the one count and then stepping back. Well, I picked that up outside of Cuba. Never in my life did I do that in Cuba. I ended up in the transition position (it has other names depending on who teaches it), but I went in reverse from the first step of the Dile que no. I did it in reverse. So, stepping forward on the one count was a very strange thing to me. Nowadays I’ve incorporated it, but I have been consciously implementing my vocational school Dile que no as part of reclaiming casino the way I danced it empirically to also see what other possibilities can be explored in the dance.

I have been studying the way empirical dancers dance in Cuba. The other day there was a video Jorge Luna Roque shared of a casino rueda done in Bayamo. If you watch that rueda, they don’t do anything complicated, but when I see that video, I go back to vocational school. I’m transported. Those people represent me. I identify a thousand percent with that way of dancing. And if you look closely, it’s very rare to see people dancing that way outside of Cuba.

There are certain things one notices that say, “This person is a casino dancer.” Another thing is how people start the moves. Also, the way of leading. You can tell when someone is influenced by other styles when they start a lead not by having the person do an external turn, but by having them turn in place, like in on1 salsa. There are women who I’ve noticed like to start their turns in a more static way, but many female casino dancers start their turns by moving forward.

Those gestures I mentioned are very distinctive. And they’re not done by people with cabaret training or art school training, for example. Like I said, I would have to use a video to explain it better.

DL: I understand that because I didn’t get to go to la beca in Cuba. I left after finishing the 9th grade. I took my entrance exams and everything, but I left. I had the tumbao, but it was in university when I really learned casino. In high school in the U.S., my focus was studying to get the grades to earn scholarships and go to college. I had other priorities. It was in university, in that space where I was precisely in a boarding school-like context (I was a 8-hour drive from home) and looking for something to do, that I started to learn.

I learned a bit more formally, not in an empirical way. But I’ve always tried to replicate (sometimes not very well) the tumbaos that I had seen when I lived in Cuba.

JM: Yes, but I do notice that in your way of dancing. I know you learned outside the country, but your experience in Cuba did give you a lot of training through the things you had visually assimilated. That’s why when you dance, it looks like you dance like a casinero. You already had a lot of visual references consciously and unconsciously registered mentally.

DL: That’s what I’m saying: I’m always trying to go back. I learned formally, first through Salsa Lovers, and then with the help of the MCC. But those are just learning tools. They are a start. I had to go back to the source, because that’s where what I was looking for was.

Let’s continue talking about the empirical dancer. As an empirical dancer, do you think empiricism can be replicated in a dance academy? In Cuba, we don’t do that. In Cuba, we don’t do “break down” of each count like an academy does. So, do you think how you learned in Cuba (i.e. “Do this like I do”) can be replicated in an dance academy?

JM: No. I can’t teach people to dance the way I learned. Empiricism is not replicable in an academy in that way. People are not paying to learn empirically. I can’t treat my students the way my friends treated me when they were teaching me to dance casino.

Also, the cultural context is very important. In other parts of the world, I could replicate empiricism: grab a neighbor or a group of people in my neighborhood and say, “Come on. Copy this,” if they come from societies where there is rhythm, where dancing happens. I can’t do that with a Canadian. But with people who come from cultures where dancing happens, I think they could have the ability to replicate something empirically.

In certain Latin American countries, for example, the results you can get as a casino instructor are incomparable. It’s not the same to teach in Europe, Canada, and the U.S. as in Lima, Peru, or Venezuela. A Venezuelan learns at lightning speed because they come from a culture that shares enormous similarities with ours.

DL: I completely agree with you. There are cultures that emphasize social dancing more; others don’t. I would also add that even within cultures where social dancing does not predominate, there are subcultures in which it does. For example, within the U.S., there is a higher probability of being able to teach casino more easily to an African American than to a white American, precisely because there is already a tumbao, some type of empiricism in the first group, which facilitates that.

What I’m thinking is that it would be difficult (almost impossible) to teach empiricism within a purely academic worldview—precisely because what the academy does is try to break everything down, go step by step, and that doesn’t represent how one learns empirically. It will create, therefore (in my view), different results. People look different when they dance casino if they have gone through an academy and do not have that background of having a previous tumbao, some established empiricism. Just as you say you recognize people who learned in boarding schools, I recognize those who learned in academies.

JM: Yes. There are talented instructors who have been able to teach their students something that makes them look like Cubans. Some little detail. I met a girl who did a very nice foot movement when she was doing her basic steps. When I asked her where she had learned it, she said her Cuban teacher had taught her. Replicating the full gesturality of a casinero, if you haven’t grown up in Cuba, requires quite a bit of personal talent and observation work on the part of the student, in addition to good teaching by the instructor.

But it is true that the subtleties are lost. And even more so if one is outside the cultural context.

DL: That’s where my conclusion is heading: the dance academy, with whatever methodology it has (because if you are in a school, you have to have some kind of methodology)…that shouldn’t be everything. It should be the beginning. For me, what the school should do is tell you: “This is a start. Go and be in community with Cubans so you can grasp those nuances and realize that some things are done differently.”

I am a Spanish teacher. I tell my students: “I’m going to teach you words that can be understood in all countries. For example, if I say autobus everyone will understand that. If I say guagua some won’t know what I’m saying, and others will even confuse it with something else. But you have to go to Spanish-speaking communities and talk to them to understand each one’s slang.”

Going back to casino, the school can’t be a substitute for socialization, which is so important for casino (or any social dance) that you have to have with the people of that culture. Because if you don’t do this, what ends up happening is that you start to divorce the product from the people who created the product. People may begin to feel that, since this is “just a dance,” they have certain “rights” to do certain things with this product because it doesn’t need to be tied to the culture.

Many non-Cubans think they can focus only on the dance, see it in isolation from its cultural context, and not have to know anything about the culture. Why? Because it has been taught as something entirely encapsulated within the academy, with no cultural context beyond it. And I do not see many academies telling their students: “What we are doing here is artificial. I want you to learn enough to go and be in community with Cubans.” If they did this, people would start truly learning the nuances of casino, bringing out their tumbaos.

I think this is lost when you think of the academy or dance school as the beginning and the end. In fact, many academies sell this idea: “Just by coming to a six-week course, you’ll be an amazing dancer.” It shouldn’t be like that. It should be more like: “This is a six-week course to give you an idea, but you have to go and be in community with Cubans.” If we don’t push this approach, Cubans will gradually start to be displaced to the periphery of their own culture as they stop being the dance’s references.

JM: And now that reference has become complicated. With all due respect to those who do it, I used to organize trips to Cuba. Nowadays, I no longer do it.

DL: Tell me a bit about why you discontinued the trips to Cuba.

JM: I used to organize them and tried to offer my students the most cultural experience possible: we stayed in private homes, I arranged classes with some schools. But most importantly, I organized social events. I sought out casino dancers and organized outings, and we would all go out to dance and share together. It was beautiful. We were connecting with the local culture.

I decided to stop because things are complicated in Cuba right now. On the one hand, anything can happen. While traveling there, a social upheaval could occur and we could get stuck there. Secondly, the precarious situation in the country. My friends in Cuba nowadays are going hungry. When I used to travel to Cuba, my friends from school and university were all struggling, but they had hopes for improvement. Everything changed drastically after the pandemic.

Because of my values, I don’t feel good about taking groups of people there and giving them an experience completely disconnected from reality. If I were to take them, I’d have to feed them properly. So, I don’t want them eating much better than my family and friends in Cuba. It seems a bit cruel to me that my people are going hungry and the people who go on the tour don’t even notice.

For me to take people there, it would have to be a guerrilla-style tour, where everyone knows there will be blackouts, you eat what you can, and you live like a Cuban. And I can’t charge someone for such an experience. [Laughs]

On the other hand, nowadays it is difficult for me to offer an authentic Cuban casino experience within Cuba itself because I don’t have a connection with any group of casino dancers who are outside of the bad cultural tourism. To take my students to share with casino dancers, I no longer have good options because I have been to Havana many times and currently the casino dance scene in these places frequented by tourists is a circus. All these places are full of clowns trying to impress tourists and doing anything.

I hear there are still social dance venues mostly frequented by Cubans without ties to tourism. Let’s see how long they last or can maintain their authenticity. I would have to do a good investigation to see who to connect with, to see if there is anyone who has a casino school, a group, or a community that hasn’t been tainted by bad cultural tourism. Because only with that kind of dance community would I have a guarantee of authentic casino.7

DL: What you were telling me was something that Nicole from Dile que NOLA realized and told me in an interview. As she said, one in five Cubans in those places you refer to is really there to dance casino; the rest are there to catch tourists. And that’s a reality that must be acknowledged because tourists bring the much-needed capital to Cuba. Are you going to tell a Cuban not to go to those places and peacock to see if they get some business? No. They have to do it. It’s their way of survival.

For me, the problem is not so much what the Cuban does (something that even Cubans focus a lot on criticizing). As I said: these are survival strategies—that end up fostering certain stereotypes, yes. But the tourist who goes to Cuba does so to live a Caribbean fantasy.

JM: That impression of Cuba is changing. And this is reflected in the decrease in the number of people going to Cuba for tourism. Fewer and fewer people are going to Cuba because the world is becoming aware.

DL: But on top of how bad it is, it is precisely that idealized idea that the tourist has of Cuba that needs to be challenged. Because part of returning casino to the Cuban is also returning its context. When I lived in Cuba, there were hotels and beaches I couldn’t enter. And that is still a reality for many. Meanwhile, the tourist stays in the hotel they want and eats the food they want and doesn’t experience blackouts and if they get sick, they go to a hospital that has all the things they need for their care. But the Cuban doesn’t live that.

It’s what you say, I can’t, with a clear conscience, take people to experience a Cuba that doesn’t exist for the Cuban, to sell a fantasy, a romanticized vision, when the Cuban isn’t living that.

JM: I actually made a blog in response to this idea that arose when Obama reopened relations with Cuba. People started saying: “I need to go to Cuba before it changes.” I’ve been raising awareness among my students about why that’s so wrong. Everyone goes to Cuba to enjoy Cuba’s capitalist past, not communism. They ride in American cars, admire pre-socialist and colonial architecture. They participate in capitalism, in colonialism. They go to listen to Buena Vista music, which is what they are fed—a music that was made in Cuba a long time ago.8 People go to enjoy the past. No one goes to immerse themselves in the system. Seeing a Che poster means nothing because it doesn’t affect your life.

DL: In fact, some of them might even have a Che shirt.9

JM: [Laughs] Look, changing the topic a bit, an act of myopia on the part of us Cubans living outside and inside Cuba is not realizing that non-Cubans, deep down, want to dance like Cubans. We’ve adapted what we do to all these other dance styles (cumbia, on1 salsa), without realizing that reality.

Let’s remember that I teach casino classes in Vancouver, Canada. Every time I’ve decided to take an action to root myself more in my culture, I’ve always been successful. When I decided to start teaching casino stepping forward on 1, I didn’t lose students. I simply told everyone: “Look, I was teaching this style. There are people who dance like this, but it doesn’t represent me at heart. From now on, I want to get closer to my identity as a casino dancer and I want to teach you, as closely as possible, how I learned to dance casino in my native Cuba.”10

I didn’t lose students even though I decided to go against everything you see in the environment. It’s not easy to adapt to an environment where no one dances like you. When I started going out to dance here, I felt the need to start doing those “cumbia” steps to be able to dance with someone because there’s no way they can follow you. We Cubans have created a dance (casino) completely different from how people dance salsa styles.

DL: Yes. I’ve noticed quite a bit on pages like DC Casineros, that when they post videos of people dancing casino, there are always comments from other Latin Americans who process casino through a salsa lens. And they comment: “This isn’t salsa” or “That’s not how you dance salsa”; or “Are they walking or dancing?”

Of course: it’s not salsa. That’s why it’s so important for Cubans and those who support Cuban culture that we call casino “casino.” That is, to separate casino from salsa. Because if you don’t, you open the doors for misunderstandings, where someone, for example, from Venezuela, starts mixing casino with how they dance salsa in Venezuela (and call it “salsa casino”). No. If you want to dance casino, you have to admit it’s a Cuban dance that has nothing to do with your experience. And you have to use concepts from that dance.

JM: And when we dance in a way that doesn’t correspond to the romanticized vision others have of our culture, they are surprised. If you don’t clown around or do typical gestures of a stage dancer, they say you don’t dance well, and other nonsense. But beyond that, there is a growing number of people who do appreciate our culture. And I say again: people want to learn to dance like us. Like the ordinary Cuban dancer from the people. It’s we who sometimes don’t have the vision and fail to properly instill our culture in those people who are interested. In that sense, we are unnecessarily losing out.

DL: I would also say it needs some nuance. I understand what you’re saying. But in Cuba, say you have your academy and someone comes who dances salsa. And you say: “This is casino, not salsa.” And the person says: “I came to learn Cuban salsa. I’m leaving.” What are you going to do? Let them leave when you need to eat?

JM: I think if people are explained that this is Cuban culture and that you are going to guide them in an immersion that will help them really dance like us (because they want to dance like us), yes: you might encounter an arrogant foreigner who wants to impose their worldview; but I would say most want the opposite. Most want to learn how to dance authentically in Cuba. That’s why we are gaining ground with our proposal to return to authenticity. People want to dance authentically.

There is also a fairly controversial issue in this regard, and that is what we Cubans ourselves are doing: many instructors are teaching their students to dance like PERFORMERS and not like SOCIAL DANCERS. In principle, everyone who signs up for dance classes with a Cuban should be informed, or have clear, what their instructor will turn them into. People generally take dance courses to be social dancers. A minority wants to navigate the rigorous path of being a performer. On this topic, I could elaborate much more.11

DL: I agree with you. But there are also other factors in Cuba. If you go to Casa del Son in Havana (whose owner, ironically, is not Cuban but Spanish), the place promotes a foreign perception of Cuban culture. In other words, Cubans are not controlling the information coming from there.

JM: It’s a matter of empowerment, not only financially, but also with skills and knowledge. Look at us and why we are successful: because we are empowered Cubans. We know how to write, draft an article, present our truths, create audiovisuals; we know how to convey a message coherently. That’s why we succeed in creating this space for authentic casino – a space that others cannot create. It’s a battle of education and persuasion. If we are going to bring about change, it’s mostly those who have the ability to propose a message and support it in various ways who can do so.

That tourist who goes to Cuba with the vision of starting a business – whatever it may be – that tourist is completely empowered. The local Cuban is at the mercy of all these forces, and the factor of needs comes into play. It’s like when someone is in a dependent relationship.

From outside the country, we can help change things so that when tourists arrive, they can say, “I want to learn the authentic casino danced by ordinary Cubans in Cuba.”

DL: That’s why having these conversations is important. We need to be aware of the unbalanced power relations that exist when a tourist goes to learn casino in Cuba. The tourist comes with their ideas and their dollars. For the Cuban, if they want the tourist to take their classes, they can’t create an idea that is completely separate from what tourists already think is “Cuban.”

JM: And that’s what we’re going to change.

DL: Exactly. And to change not what the Cuban does (because the Cuban is simply responding to something that is already happening), but to change the mentality of the tourist, so that they go to Cuba knowing how to authentically dance casino.

Now, my question is: do you think that the lack of coherence in how casino is taught to tourists in Cuba (not empirically; casino has been taught empirically among Cubans for decades) is an extension of–let’s say–an inferiority complex that we may not have processed as such, but that through our experiences in Cuba we have internalized in certain ways?

Let me explain. Cubans are not allowed to enter some hotels where tourists stay, or they are asked for ID before entering the hotel–when tourists are not. They can’t go to certain beaches that are for tourists; they experience blackouts while tourists never suffer power outages in their hotels. In other words, Cuba is not for the enjoyment of Cubans. So, do you think what’s happening in Cuba, in terms of the people teaching casino to tourists, is a reflection of the idea that: “Well, why teach them casino as I dance it if these people have never come to the Cuba I live in–and in fact the system itself sees me as a cockroach, because it doesn’t let me enjoy my own country?”

JM: I am a hundred percent in agreement with that. Besides the unequal power dynamics established between tourists and instructors, how can you expect us to have the empowerment to tell someone visiting Cuba, “Look, this is our culture. I invite you to learn it the way we live it,” when we are a people without dignity, crushed? We have no self-esteem. The Cuban is an abused person. We are so used to having our dignity trampled upon that it’s the most normal thing. This issue of catering what a foreigner wants is neither questioned nor processed. You’ve got to get those dollars, no matter what.

Also: there’s also the ignorance that comes with empiricism. I repeat: it’s difficult to transmit culture. One opts for the easiest route, by looking at what others are doing, replicating and amplifying these paradigms. Teaching authentic casino is not easy. It requires deciphering it. One of the most frustrating experiences is trying to break down motor skills learned empirically. That’s why copying what other instructors are doing, being the easiest route, leads to replicating errors and ways of dancing that aren’t truly Cuban. Some of us have already begun the work of offering a more Cuban way of dancing Casino; what we need is for it to be amplified.

DL: I would say that this amplification has to come from ourselves. We don’t have to wait for it, because they’re not going to give it to us. Few social or cultural change phenomena start from the top. Every change begins with a group of people coming together and saying, “This needs to change. We have to unite as a bloc and set aside our egos.” We have to share what we do. To say on my page, “Hey, follow Julio,” and you on your page say, “Hey, follow Dáybert.” And so on. When people see that there’s a whole group acting with a coherent mission, it will be impossible to make that invisible, or label what we say as rants.

JM: And it’s true that we’ve been gaining ground by putting material online. We’re showing the world what we do. It’s very important that there’s intellectual content supporting all these things. Hence the great importance of the work you’ve been doing all these years because Son y Casino is a reference for everyone interested in authenticity, in the necessary revisionism our culture needs after many years of neglect.

And I understand that sometimes it takes time to reorient oneself. I was disoriented for a long time. It took me twelve years to pick up my casino again. When I started teaching here, I learned from a Cuban named Armando (from Havana) who was already giving classes. He was a tremendous casinero as a social dancer, but when he taught, he applied this whole system that has spread like a virus, the Salsa Lovers’ system, with that backward stepping and even doing a Guapea totally frontal and not in an open position. It was very different from how I learned to dance. Growing up in Santiago de Cuba, I assumed that the style Armando was teaching was a regional way of dancing casino, typical of the western part of the country.12

I had to do my research to realize to what extent stepping back on the one is Cuban. Because not all ways of stepping back on the one are Cuban. There are things that go beyond what my mom would do, who does step back on the one because she is a first-generation casinera influenced by son. If you don’t take the time to observe, if you don’t dedicate time to studying videos of ordinary Cubans dancing in Cuba, you can go for years without realizing this. For me, in teaching my more advanced courses, there always came a point where I had to teach my students to step forward because there are figures that can’t be done if you don’t walk.13

DL: Speaking of things that happen outside of Cuba, as a Cuban, personally I’m seeing that there are non-Cubans who don’t know anything about my culture, who aren’t in community with us, and they’re teaching our dances. How do you feel about that?

JM: Obviously, it bothers me to see someone trying to make a living off my culture disconnected from it as such; disconnected from the Cubans who have already been working on promoting that culture and doing a good job. I’m concerned about how people are treating Cuban culture with a capitalist jungle mindset, and that’s how they’ve articulated it. People who consume Cuban culture dissociated from it and dissociated from the Cubans who represent it see our identity as simply entertainment. For them, this is just a dance, and they just want to dance. In that simplistic way, they articulate their ignorance shamelessly, and publicly.

Look, in late 2023, I had an issue here in Vancouver with some students who formed a clique through which they completely dissociated from the overall objective of my work here as a Cuban, which is to promote my culture and generate recognition for its vital contribution to life in Canada. They formed a clique that didn’t care about scheduling a Cuban event on the same day as another Cuban (who has been promoting Cuban culture here for almost 20 years), creating division and undermining the efforts of the latter to promote his culture. Here you can see how they didn’t see themselves as part of a community around Cuban culture, but simply as “a group of friends.” This deep disconnection and view of our culture as mere entertainment, coupled with indifference to how the dispossession of our culture impacts Cubans, justified by libertine arguments, is what you identified earlier, and it happens within dance schools.

In this sense, I criticize myself a bit for perhaps not having done more to educate my students, but we must acknowledge another more perverse and depraved factor that affects Cuban culture and its dissemination outside of Cuba, which is the fact that some people use Cuban culture to feed narcissistic impulses and position themselves in power and leadership within a specific group. I’ve seen these aberrant relationships flourish everywhere, and for us Cubans, it’s very easy to identify them because we have an instinctive/intuitive ability to know when someone genuinely cares about our culture. How many people have become casino wheel choreographers, not out of love for Cuba, but to become gurus of a group of people? I’ve seen this here in Vancouver. And what can I say about schools that literally exploit Cuban culture without producing a single competent casinero? There’s a school here that has been exploiting Cuban culture for years without contributing a single casinero to our community.

I find solace in the fact that all these individuals are destined for failure and eventual sterility due to an inevitable reality, eloquently articulated by an artist whom I used to admire (no longer), who said: “Only love begets wonder.”

I criticized these relationships towards my culture as parasitism, and that’s exactly what it is. The curious thing is that the leader of this clique is part of a cultural group where they perform traditional Aztec dances. Imagine if I were to learn those dances and say, “Now I am an instructor of traditional Aztec dances. I am free to do whatever I want because the Canadian constitution gives me the freedom to do so.” How would that sound to Mexicans?

There are limits in life. Our culture has created a product so popular, so joyful, so easy to embrace, that many people believe they can just claim it as theirs.

DL: Yes. And two things there. The first is that for Julio Montero to be an instructor of traditional Aztec dances, you would have to be deeply integrated into the Mexican community for them to accept you as someone who can do that. And that takes a lot, a lot of time. And second: I think what you’re elevating here is a ramification of the lack of empowerment we talked about. “You want to take over the casino for yourself? Go ahead. Because in the end, in Cuba, nothing belongs to us.”

Perhaps this is happening because we’ve gotten used to people grabbing and grabbing and grabbing, and we haven’t stood our ground anywhere (because standing our ground could mean losing business, for example, or becoming the villain; you’re not “friendly”). So, we’ve accustomed people to do as they please with our culture. And if we have the courage to say, “I am Cuban and this is my culture and it deserves respect,” they say…

JM: They say you’re causing division.

DL: Exactly! That you’re divisive.

JM: But it’s not the majority who see you that way, you know? The tiny minority is the one accusing you, the noisy, vocal, triggered ones. I can confirm from my own experience that the vast majority of people perfectly understand the Cuban’s right to own their culture and demand a healthy relationship with it. They agree with you, but they don’t get involved in the drama. Those who participate in the drama are the ones who have something to lose when a Cuban like me stands his ground. Who are they? The narcissist, the sectarian guru, the owner of a dance school that exploits Cuban culture and needs it not to be claimed by its people. The people who confront and antagonize us are the ones with an obvious interest in using our culture for personal gain. Otherwise, they would leave us alone, end of story.

Another factor at play here is the level of education of the people. In my case, when I stood my ground, yes: some accused me of dividing. There were very, very few people who never took classes with me again. I knew all that would happen. I know that a lot of ignorance towards my culture would surface. But I said to myself: I am clear that this is wrong. It is very wrong for you to train in my school, form a small community of friends, and decide to start competing with Cubans themselves, whose culture you are benefiting from. You have to collaborate with the people who produce the culture from which you have made a lifestyle. It’s a matter of GRATITUDE AND RESPECT.

In this business of cultural transmission, ethics must play a significant role. It’s the nature of this business model. We are being affected because many non-Cubans truly believe they don’t need validation from Cubans to transmit and monetize Cuban culture. This is the ground we must reclaim because there is a risk that Cuban culture, already diluted, will continue to be diluted even further. Many ethical parameters need to be observed.

What I want you to know is that standing your ground, contrary to what many Cubans think, associating it with losing business or students: it’s really necessary and positive. It’s good business! Seven months after what happened, I still have a ton of students. I insist: a ton of students. My school continues to thrive and people are happy.

The other thing: using certain terms and expressions dissociated from our culture with a form of dance that is also dissociated from it is a problem. Perhaps that’s why months ago you came up with using the term “Cuban salsa” to address the issue.

DL: Precisely. What I was seeing was very detached from casino and resembled more linear salsa. That’s why I started saying “Cuban salsa,” not as a synonym for “casino” (as it was understood before), but as something different, with some aesthetic similarities, but different.14

JM: The first thing I tell my students is that our way of dancing what is known as Cuban salsa—casino—is the only style that truly represents a Latin American culture. That’s the first distinction I make to them. The salsa styles from LA and NY, none of those represent a Latin American nation. And it’s based on that distinction that I establish the respect that should exist towards casino as a dance that should part of the Common heritage of humanity, and is part of the identity of a nation.

Therefore, whoever teaches it should do so properly.

DL: Correct. And if they don’t want to worry about these cultural aspects, they should dance (and teach) linear salsa!

JM: Exactly. Dance that. No one will be offended. You won’t upset anyone from New York or Los Angeles. No one will jump out at you.

In principle, I wish there were twenty casino instructors throughout the Vancouver area. We could change the scene, and it would be something beautiful. I’m already contributing to that. I’ve just redefined my school. From, “Julio Montero, Dance Instructor” it became, “Julio Montero, Dance Umbrella.” I’ve decided to empower a group of very dedicated students who have expressed interest in teaching by sharing my methodology with them and bringing them into my system to expand the teaching of casino across various parts of the city. In short: a person who is not Cuban can teach casino, but they must be well-informed on the subject and validated by Cubans who do possess the knowledge.

(A brief aside. There’s controversy over who is qualified to teach Cuban traditional dances, specifically casino. Some graduates from art schools have wanted to monopolize teaching this dance to which they never paid attention, and have tried to use the “professional dancer” label to discredit those who teach casino, who often are not graduates of these institutions. It’s important to break that paradigm. The ironic thing is that people like you and I are qualified because we have at least studied teaching methodology at the university level, while graduates from ENA do not receive thorough training in pedagogy. Perhaps this is a topic for a specific article.)15

Another thing, beyond ethics towards our culture: no one deserves to be deceived. If someone comes to take a casino class (or sees the term “Cuban salsa”), it’s because they want to connect with our culture. We have an obligation to offer them something that is Cuban. You can’t deceive people shamelessly, especially when you took classes for a year, didn’t pay attention, did whatever you wanted because all you wanted to do was dance, and then decide to become an “instructor.”

One thing I’ve noticed in our favor is that informed criticism works. It’s just that you have to criticize with arguments, with information that raises awareness. I’ve noticed that when someone wants to be an instructor of Cuban dances and a Cuban comes and tells them, “What you’re doing is crap,” it’s like a bucket of cold water. We must start from an appreciation standpoint towards those who are interested in our culture and help them because due to lack of guidance, education, or whatever, they are not doing things right.

Collaborating with us is so beneficial. If you collaborate with Cubans, you can benefit from so many things, especially if you want to get into the teaching world. For example, I can provide guidance, you can educate yourself thoroughly on teaching casino, you can enjoy all the benefits enjoyed by members of my “umbrella”; they can say they are supported by me and my methodology, which has proven to create good dancers, etc., etc.

DL: Another thing that can happen—and I’m going to write about this at some point—is that the person hasn’t thought about their own identity and privilege within a space, which leaves us on the periphery.

Imagine a promoter comes with a Cuban group and contacts that person from the clique you mentioned to accompany the group dancing. And that person, who doesn’t represent the culture and hasn’t done the work they should, instead of telling the promoter to contact you, the Cuban who has done the work and does promote Cuban culture, starts representing our culture. This is super problematic.

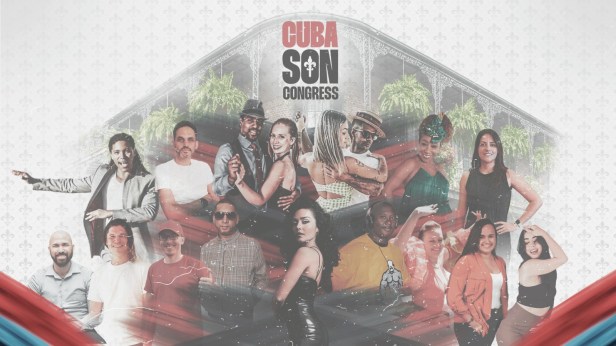

Well, speaking of giving prominence to Cubans, let’s talk about Cubason Congress, which this year will be taking place in the city of New Orleans from August 8-11. You will be teaching there.

JM: What fascinates me about this event is that, at Cubason, the casinero has finally found its space. I don’t know how many other festivals exist out there where the atmosphere truly feels like it belongs to casineros. In the world of Cuban dances, everyone, according to their interests, has been finding and creating their own spaces. There are events that, for me, are quite eclectic. There are others that are more about showbiz (people in the fusion world, those who want to dance like performing). There are rumba festivals. There are others for people obsessed with rueda de casino.

I went to the first international edition of Cubason, there in Playa del Carmen, and I have never felt so comfortable at a festival. I was there with people who spoke my casinero language—with an accent, but recognized my language. I was there being myself: a casinero.

I think Cubason is creating a space for which there is demand. Many people feel out of place at these other festivals, especially those where people dance in a somewhat narcissistic manner, as if it were a performance. This goes against the nature of casino. Casino is a dance where, due to its dynamics, you immerse yourself in your own world with your partner and you don’t care about what’s happening around you. If you want to impress someone, it would be your own partner. It’s about personal enjoyment. You’re never thinking about an external eye watching you. That’s not the case at these other events. That’s why I’m super happy that a space has been created for the social dancer. The folklorist already has their space; the rumbero has their space; the cabaret dancer has theirs; the ruedero too.16 Now we pure-blooded casineros (and soneros) finally have ours.

DL: What you’re saying is exactly what Nicole Goldin said when I interviewed her: Cubason is a space for the social dancer, not for the performer, those who do fusions, or for those who do “rueda” but don’t dance casino (that’s another conversation); it’s primarily a space for the social dancer, which is much needed.

And let me tell you something else, since we talked about empowering Cubans earlier and you’re working with a similar concept with your “Dance Umbrella”: one of the things we should do at Cubason is come out of this event with guidelines that say, “Do you want to teach dances from our culture? Do you want to be supported and validated by us? Great. Then you have to follow these guidelines.” If, as Cubans, we want to take back control of the narrative about our own culture, we have to do something like this.

Well, Julio, we’ve been talking for two hours and there’s much more to discuss. We can continue talking. These conversations will continue in the panels at Cubason. There will be a panel for us Cubans, where we can discuss what we see happening with casino outside of Cuba.

JM: I want to end this conversation by sharing something optimistic. At the University of British Columbia (in Vancouver), there’s a casino rueda club that’s been operating for over fifteen years. It’s called “UBC Salsa Rueda Club.” The other day, I spoke with the new president of the club and he said to me, “Julio, we’ve been thinking about changing the club’s name to reflect Cuban culture.” And I was surprised. The young man has been asking me questions about the history of casino (I directed him to your blog), about the history of timba (I directed him to timba.com). The fact that this interest came from them excited me. Similarly, seeing the interest they’ve shown in implementing a way of dancing that’s closer to the reality of Cubans had a very positive impact on me because the idea came from him.

I wanted to share this with you because it’s what I’ve been telling you: most people who are interested in our culture, deep down in their hearts, want to be authentic. They want to be true to our culture, and it’s up to us to help them for the benefit of all.

Notes:

- For more on this topic, click here. ↩︎

- If you want to know more about what I am referring to, click here. ↩︎

- In Cuba, “beca” refers to schools where students attend grades 10 to 12. They are effectively a board schools, located on the outskirts of cities. Students would spend most of the week there, and return home during the weekend. Other names for “la beca” include “el pre” (or pre-university) and “la vocacional.” ↩︎

- Do you have a lot more time to read? Well, then check out the thousands of comments that Cubans left on this video, which showcased precisely what Julio is describing: learning casino in these becas. ↩︎

- For a super interesting and scandalous story concerning the duo Milli Vanilli, click here. ↩︎

- The word tumbao is used in Cuba, among other things, to highlight a certain way of moving, walking, or dancing. This word was popularized internationally by Celia Cruz in her song “La negra tiene tumbao,” which is about how a Black woman walks. ↩︎

- For more on what you can actually expect while traveling to Cuba for the purposes of dancing, click here. ↩︎

- Click here for more on why focusing on the music of Buena Vista Social Club invisibilizes more current musical production in Cuba. ↩︎

- For Cuban exiles, Ernesto “Che” Guevara is a highly controversial figure. In Cuba, “the heroic guerrilla fighter” (as he is known) from Argentina is idolized. Outside of Cuba, the stories of his summary executions are more widely known. For more on this topic, click here. ↩︎

- Click here for more on this discussion on stepping forward vs. back in casino, and why it occurs. ↩︎

- I have personally elaborated on this topic. Click here to read more. ↩︎

- See Note #10 ↩︎

- Click here to understand more of the nuances that Julio is talking about. ↩︎

- For more on this topic, click here. ↩︎

- See Note #11 ↩︎

- Here it is necessary to clarify that when we say “ruedero,” we are referring to people who only dance “rueda,” and in some cases, due to the omission of the word “casino,” they see rueda as something separate from casino. Remember that the full name is “rueda de casino.” ↩︎

ABOUT JULIO MONTERO

Julio Montero, a Cuban-born dance instructor now based in Vancouver, shares the vibrant energy of the Cuban Casino dance. Raised in the historic city of Santiago de Cuba, Julio carries the rich musical and dance traditions of his homeland. His profound connection to Afro-Latin-Caribbean culture is evident in his teaching, extending beyond dance steps to convey positive cultural values. Julio’s methodology, shaped through years of study and experience, creates an immersive and joyful learning experience. Julio is a dedicated ambassador of Cuban dance.