In mid-July, I received a message on Facebook. It was from Cuba and informed me about a casino festival that was going to be held for the Cuban people in Havana. The sender’s name was Herson, and he asked me if I could help promote the event on my page, which has many followers living in the capital. Clearly, this piqued my curiosity. A casino festival in Cuba for Cubans? The ones I knew were mostly for tourists.

So I began to investigate, and the more information I found and read, the more surprised I was. Indeed, the Kubasoy Casino Festival was what it promised to be: a space for Cubans—not tourists—to learn how to dance casino. I had never seen such an initiative (which doesn’t mean it didn’t already exist; what I’m saying is that I personally had never seen it).

Since 2014, I have been writing on my blog about the state of casino dancing outside of Cuba. My goal has always been that the reference for casino dancing should not be a non-Cuban person teaching outside of Cuba, but rather the Cubans living in Cuba. To that end, I have tried to refocus and reframe the conversation so that people begin to see the Cubans in Cuba as reference points for casino dancing. Unfortunately and ironically, the Cubans living in Cuba have been pushed to the periphery of their own dances, overshadowed by media personalities with more resources and better platforms to showcase what they do. Today, for most people dancing outside of Cuba, the references are not the Cubans from the island.

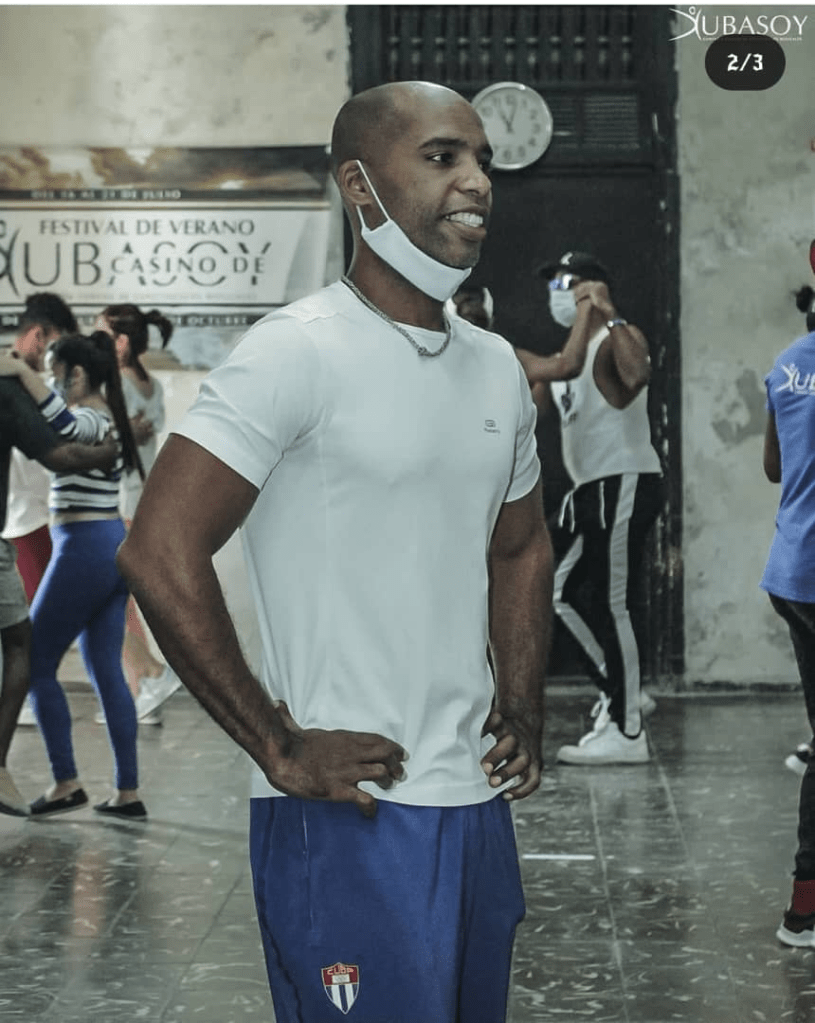

So, I was incredibly happy to be able to connect with Herson and interview him to learn more about his work. As you will read in the interview, Herson and his dance company, Kubasoy, are betting on the Cuban people.

Without further ado, here is the transcript of my conversation with Herson Fernández Machado, creator of Kubasoy and the Festival de Verano Casino de Kubasoy.

DLD: Herson, tell me a bit about your background as a casinero.

HFM: My background as a casinero dates back to 6th grade. A neighbor of mine, who was older than me, told me I had to learn how to dance casino because, at that time, it was all about using the dance to get girlfriends (“get dates” for those who aren’t Cuban). Once I started, I liked it. I didn’t find it hard. At first, I took it as a challenge. And it got to the point where, when I went to secondary school, there were still escuelas al campo.1 I remember that people would even line up to dance casino with me there, not because I was the best, but because there were very few male casino dancers, and among them were even the teachers.

After that, I attended the Lenin, where I honed my skills a bit more.2 There, we would dance even during the five-minute breaks between classes. No music. We’d dance in the hallways, in the porch, anywhere. In fact, before self-study began at 8:00, we would meet in the hallways at 7:00 to form ruedas.

At university, I became more interested in learning about the dances themselves. I always wanted to learn how to dance rumba. I learned thanks to Leonardo Martínez Molla, a lead dancer of the National Folkloric Ensemble of Cuba, who was invited to the university to teach some folkloric pieces. I was there for that folkloric session. We performed the work El Solar de Lola as part of the festival for amateur artists. After that, I became the leader of the group that was formed. It was the first folkloric group ever created at UCI (University of Information Sciences), and we called ourselves Ilú Aché. I took part in several attempts at giant ruedas and breaking Guinness records at the university in casino wheel competitions.

After I graduated, I joined a dance school for foreigners. That’s where I developed more, not so much in terms of dancing, but more in methodology. At the same time, the thought crossed my mind that I was teaching foreigners, but I wasn’t seeing the opportunity to teach Cubans. So during this time, while I was teaching foreigners, I was always looking into how to teach Cubans as well.

Three years later, I created Kubasoy, which celebrated its ten-year anniversary this year on June 14. It started as a small dance group with just four couples. Over time, it grew and became a bit more ambitious. We began to notice the decline of popular culture among the people. Kubasoy aims, in some way, to contribute to revitalizing Cuban popular culture. (We don’t say “rescue” because you rescue something that’s been lost; that’s not the case here.)

In short, we understood that this revitalization was needed, especially among the younger generations who, for the most part, don’t identify with traditional popular culture. Just because there are 10 million of us and 10,000 are studying in art schools doesn’t mean that popular culture is still thriving among the people. The rise of new genres like reparto and reggaeton is displacing our popular culture. So Kubasoy took on the task of creating a space where we try to collaborate with our popular culture.

That same year I got the group started, we held the first Kubasoy Summer Casino Festival, which was the first festival—at least in Havana, and I dare say in Cuba—aimed at Cubans, to teach them how to dance casino. I say this because, up until that point, many festivals had been held in Cuba, but they were all for foreigners.

DLD: Let’s clarify that because what you’re saying is precisely what I’ve noticed, and one of the reasons I wanted to talk to you. I know there are many festivals in Cuba, especially in Havana, where everything is geared toward foreigners—what’s taught, how it’s taught, and even the prices. But you’re doing the same thing, except for Cubans. Tell me more about the differences between the festivals for foreigners and what Kubasoy is trying to do.

HFM: There are many differences. First of all, the financial backing that foreign-oriented festivals have. On the other hand, I haven’t found a casino festival for Cubans other than ours. Not in Havana, nor in Cuba. There are popular dance festivals, but for casino, for Cubans to learn how to dance casino and rueda de casino, there’s only Kubasoy—a festival organized by the company with its own resources (which are scarce).

We, as social dancers and instructors (those of us who have been evaluated), conduct methodological training for our company members, who act as instructors during the festival. The same dancers are the ones teaching casino dancing to children, youth, adults—and even seniors, as we’ve had many examples of seniors who wanted to learn because they didn’t know how but always wanted to.

In terms of payment, although we’ve had to raise it over the past two years, it’s still very symbolic. The festival lasts a week, with classes held over six days, two hours per session (with three sessions). Anyone who wants to participate in the festival only pays 500 pesos.

DLD: I don’t know how you’re managing that. 500 pesos is nothing.

HFM: I am doing this, and I’ll be very honest with you, because it’s my small contribution to Cuban popular culture.

DLD: I really appreciate that, because if we all contributed our bit, things would be very different.

How are these festivals perceived in Cuba? I know you can’t speak for everyone, so maybe the better question is: How do you perceive them? And what are the real consequences of the pedagogical resources for Cuban social dances being used for foreigners instead of Cubans?

HFM: I’ll give you my opinion. Obviously, organizing a festival generates a lot of things. These festivals are generally focused on foreigners because they bring the money. In Maykel Blanco’s festival, the Salsa Festival, Cubans have access to the concerts (whether the price is affordable or not is a complex issue, given the country’s economic situation). But most Cubans can access it. Whoever can afford the ticket goes to the concert. But festivals like Ritmo Cuba, Baila en Cuba. Cubans don’t have access to those because of the cost.3 Perhaps a night of concerts at Ritmo Cuba costs you between 20-40 euros. Very few Cubans can afford that for one night of concerts. And if we’re talking about everyday Cubans…well, practically none of them can.

DLD: What’s the monthly salary in Cuba, converted to euros?

HFM: Normally, a basic salary in Cuba is around 4000 pesos a month. If you convert that to the government’s exchange rate, I’m not sure exactly what it would be because I don’t have that information. The government doesn’t make those conversions for you, so you have to go to what we call the “black market,” and here there’s a sort of parameter set by a website called “El toque”,, which gives you a better idea.

DLD: I checked El Toque, and it says that 4000 Cuban pesos is worth 11 euros.

HFM: That’s what a Cuban earns per month. It barely gets you by. Imagine paying for a concert on top of that. It’s just not possible for the average Cuban.

DLD: And that’s what I want people reading this to understand. When foreigners come with capital, they often don’t realize what that money represents. It creates a kind of microcosm at these festivals where the foreigner might wonder why they don’t see more Cubans beyond the instructors. That’s why.

HFM: At Ritmo Cuba, we’re invited to the festival. Most of the festivals are for foreigners and marketed to them because the average Cuban simply can’t afford to attend. Beyond that, when Cubans do pay, it’s in the national currency, which foreigners can’t use for anything because it’s not recognized (or has no value) internationally. So, if a foreigner wants to host a festival to raise funds, they’re not going to do it using the national currency.

The Kubasoy Casino Festival is for Cubans, not about making money from the festival. When I created it, the idea at the time (which is no longer the case) was that it would be supported by cultural institutions because, after all, it’s educational and aligned with a cultural policy aimed at preserving our traditions and for the people. Nowadays, the festival is funded by whatever I can do, and the help I get from friends… that’s how it works.

DLD: You mentioned that you haven’t received support from cultural institutions for your festival. Tell me why that is.

HFM: Honestly, I don’t know. I’ll also admit I haven’t focused on why they don’t support me. I’ve focused on just doing it. I’m more of a person of action than words.

The Kubasoy Casino Festival has become our little child. It’s our baby, and we try to do our best with it. We take a lot of pride in this festival because, for me, it’s something unique in Cuba. No one else has it. No one else does it. Maybe someone will come along tomorrow and do it even better than us, and we’ll be left knowing that we were the driving force. Still, we’re filled with joy by the many experiences we’ve had over these ten years, with people coming in not knowing how to dance, unable to even identify a rhythm.

I have an anecdote from the first year. I remember a man, 89 years old. His name was William (or maybe still is; I don’t know if he’s passed away). Back then, we did everything in a community cultural center. He came up to me and asked, “Do you think I can participate?” I told him, “Look, sir, anyone who believes they can dance is welcome to participate. We don’t discriminate by age or gender.” He replied, “I’m 89 years old. I don’t want to die without having learned at least how to dance casino because it’s the one thing I couldn’t do, and I always wanted to.”

These are the stories that stay with you from something you did for society, for your culture. That man, at 89, was able to learn casino thanks to the Kubasoy Casino Festival. So, why haven’t I been supported? I really couldn’t tell you. The reality is it hasn’t happened. I haven’t focused on the “why” because I feel like it would drain too much of my energy and take up too much of my time.

DLD: It’s quite sad that this is happening. As you mentioned, and as I’ve seen as well, I haven’t seen another initiative like this anywhere in Cuba. I don’t understand why cultural institutions wouldn’t want to support a project like this, where the goal is revitalization—something these same institutions constantly say is needed.

Anyway, let’s talk a bit about the methodology you use. You were self-taught, but you also taught at a school for tourists. Personally, I’ve noticed that in these schools, they often adapt to the way tourists think Cuban dance should be done, leaning toward the linear paradigm of salsa. And I see many schools in Cuba adjusting to this. My question is: what methodology are you employing to ensure you’re fostering the casino that’s always been danced in Cuba, not a casino, so to speak, “tainted” by foreign elements?

HFM: I’m a pretty analytical person. The methodology we used at our school was very effective. Maybe I didn’t agree with some terms, specifically because they were aimed at foreigners, like the so-called “musical time 1,” which has never been seen in Cuba.

In my case, I don’t dance on the “time 1” of the music. I dance in musical time. The “time 1” of the music is more tied to the musical structure. Musical time is what we call “the pulse,” which is what a Cuban dances to. A Cuban finds a beat and jumps in. The foreigner looks for the beginning of the musical phrase to start dancing. The Cuban don’t do this. That’s one of the things I maintain in the tradition of casino, besides not calling it “salsa.”

In terms of the learning methodology, it was very effective because the goals were well broken down, and you would get there. If it works, let’s improve it. I’m not going to try to do anything new if something already works. I tested that methodology with Cubans, adapting various things because I also looked into traditions and how I learned. At the same time, what has also happened due to commercialization is that many moves have undergone changes, where in the end, it’s the same move, but “Pepe” arrives in Paris and, in an attempt to call it something new and different, simply changes the name. So a “Dile que no” there is called “Camínala” (just to give an example). This has resulted in the same move having different names. That’s not so bad because the same thing happens in Cuba itself. But casino dancing has been mixed and stylized a lot in order to sell. Once a student has learned how to dance casino, what else are you going to give them? They’ve learned already. So, they’ve started blending more with elements of African origin in order to sell and continue to have students.

There’s a marked sense of selling because people have to make a living. Up to a point, it’s justifiable.

DLD: I always say: you have to eat. And that’s part of my work outside Cuba: trying to make people aware that when they go to Cuba to learn from you all, the Cubans in Cuba, you don’t have to do that. Instead, you can sell casino as casino, as part of a cultural tradition, not as a personal necessity.

Tell me a bit more about how you see casino within Cuba.

HFM: Casino in Cuba has gained more momentum lately due to the recent records set for the largest number of wheels and dancers simultaneously. In fact, I was part of the organizing committee—and the main organizer here in Havana—along with the project Retomando el Son, Bailando Casino.4

But well, that was a push focused on breaking the record. Now we have to see if it keeps happening. Kubasoy’s revitalization efforts work mainly from a contemporary standpoint. Let me explain. Today, if you play a mambo by Dámaso Pérez Prado, the first thing people will say is that it’s old. New generations don’t identify with that music. And it makes sense because it’s from another time. What does Kubasoy do? Well, we take a song like “Toda una vida” by Leoni Torres, which very few people identify as a son, and we teach people to dance son with that song. And since people identify with the song, that’s where we hook them in, and we teach them how to dance son. And after I’ve “won you over,” I say, “The one who created this was this man…” And then I transport you to the past, to the origins, to the foundation. But first, I take you through a contemporary process.

In most cultural centers, they work with the old stuff. That is, with the creators or main exponents of the genres: Prado, Jorrín, Pacho Alonso, etc. What we do is look for this music performed more recently. For example, a chachachá by Manolito Simonet, a son by Havana D’Primera—something with which the new generations can more easily identify. Doing it this way has worked for me.

DLD: I think that’s a great approach. You want people to know the tradition, but you lead them there in a different way.

HFM: My goal has always been for people to learn how to dance. Maybe the student doesn’t know who’s playing the music. But if you can identify the rhythm, you can dance to it. What I need is for students, beyond knowing who created the mambo or the cha-cha-chá, to actually dance to these rhythms. Sure, I explain who created it and when, but my goal is for these rhythms to be danced.

DLD: We talked about casino within Cuba. Do you have any knowledge of what’s happening with casino outside of Cuba, through social media? What do you think about that?

HFM: I haven’t only seen it through social media. I’ve also traveled and taught classes abroad. In some way, I have enough knowledge of how things work outside.

Now, to say if it’s “wrong” or “right” is not really within my scope. I’m quite respectful of the work of many colleagues.

DLD: Let’s put aside the dichotomy of “right” and “wrong.” That’s not my focus either. What I want is for people to understand that what’s being done outside is often, as you mentioned, because people need to make a living; they need to sell. Not necessarily, in those instances, are they looking to reflect how casino is danced in Cuba, like you were telling me about how in Cuba we don’t dance based on the beginning of a musical phrase.

HFM: As I said before, people need to sell. They need to get students. They need to make a living, build a positive reputation. For this reason, casino has evolved significantly. Maybe what they’re dancing abroad isn’t casino anymore; maybe, at some point, it will take on a different name. Anyway, it has developed very rapidly.

There are Cubans today who have really advanced in their dance skills. They’ve learned various dances, have known how to fuse them, and now foreigners see that as something remarkable.

DLD: What you just described, these are very personal, individual trajectories: a person who knew how to fuse these dances in a certain way is just that person and no one else. It’s not a broader representation of how casino is danced in Cuba. I like to highlight that because, yes: there are tremendous artists who can fuse many dances. But that’s the idiosyncrasy of that artist, not necessarily a representation of Cuban dance. I don’t know if you agree with that. That’s the way I see it.

On this matter, philosophy and respect are key. Every person is their own world, and each has the right to their own opinion. I try to give you my perspective on what I consider “Cuban.” But the teacher who understands it differently, who am I to say if they’re right or wrong? It’s just their point of view. Now, if you say it’s Changó and what you’re dancing is actually Oggún, then you don’t know what you’re talking about.

I respect all philosophies, just as I hope mine will be respected in return. I tell my clients when I have them: “Cubans care about enjoying the dance, while you care about quantity. That is, your philosophy is that the more moves you know, the better. For a Cuban, it’s not like that. The Cuban focuses on enjoying the partner, the music.”

So, these people want to look like Cubans, but what they don’t understand is that Cubans don’t do things for the sake of quantity; they do it to enjoy what they’re doing. If you focus on move after move, there’s no way you can enjoy yourself.

And another thing: it’s the man’s responsibility what happens on the dance floor. If the woman doesn’t know the steps, it’s our duty to guide her. If we’re with a friend who knows how to dance, we don’t want her to be left sitting. We invite her to dance. And that friend will, at the very least, be able to do the basic steps if I guide her. Both of you will enjoy it. Even if you didn’t do all the moves you wanted, you made a friend dance and enjoyed that moment. My goal is to find what a Cuban feels when dancing. The Cuban isn’t thinking about the moves they’re doing.

DLD: Let’s switch topics a bit. I saw on the Kubasoy page that you also hold events at El Sauce. Can you tell me a bit about that space and how it differs from other venues that could be considered similar, like Casa de la Música or 1830?

HFM: Honestly, there aren’t many differences. Perhaps the main difference is that at El Sauce, the idea is to create a space primarily for Cubans. The “casinero” parties are events we organize as a company. We have raffles and something we call a “rueda de chupito,” where the person who makes a mistake in the dance circle has to take a shot. In fact, we managed to get Havana Club to sponsor one of these parties, which is a partnership we hope will continue to grow, since we’re talking about Cuba’s national rum. But of course, at some point, people start making mistakes constantly [Laughs].

At the same time, we also include space to teach a dance move or some steps, and we invite everyone to participate in that mini-class.

The company is both musical and dance-focused. In addition to putting on shows with both recorded and live music, the musical group within the company also performs popular dance music concerts. But again, the main focus is that it’s for Cubans. It’s not that foreigners can’t come, but it’s a space for Cubans.

DLD: That’s what I noticed. In the videos I watched, I saw that the vast majority of attendees—if not all—were Cubans. And for me, it’s important to have these spaces, clearly for Cubans, but also for someone who travels to Cuba, knows how to dance casino, and doesn’t want to go to places packed with tourists where there are different dynamics. If someone wants to dance authentically with Cubans, I think this would be a fantastic space.

HFM: It’s not that you can’t dance authentically at 1830 (just to name another space). The thing is that this is a space for foreigners, catering to them.

But as I said, El Sauce is for Cubans. In fact, we invite ruedas de casino that want to perform there with us. We invite the casinero leaders who want to be a part of it. The atmosphere is a bit more Cuban. If you want to dance among Cubans, it’s a good option.

DLD: Once this conversation is published online, people reading it may want to go to El Sauce, precisely looking for a deeper connection with Cubans. What advice would you give to those who want to approach this space with a bit of cultural respect for Cuba and Cubans?

HFM: Well, the first thing is that I would not stop focusing on Cubans, no matter who shows up. At least at El Sauce. It doesn’t matter who comes, the focus of this space will always be on Cubans. For example, we’ve managed to offer table reservations at reasonable prices. The idea is to maintain a space for Cubans, with a healthy casinero atmosphere, where people can enjoy concerts, a small show, have a drink, and dance socially.

DLD: I also saw that you appeared on a Cuban TV show called “Hola, Habana,” and I find it impressive that you’re on Cuban television, even if it’s a local channel. Tell me a bit about how that came about.

HFM: That came through a contact who reached out to me to promote something. The channel’s director liked the way I expressed myself and asked if I had been on TV before. I told her that I’m a dancer. I also explained that I’m a computer engineer and teacher. She asked if we could do something with casino during the holidays, and I agreed. And that’s how we started. Initially, it was just for July, but it extended into August because it seemed like the idea of learning how to dance casino was well-received. According to the show’s presenter, people have given very positive feedback on that part of the program.

In terms of marketing, having 6-7 minutes on television is very positive because, among other things, it raises awareness of the work we are doing.

DLD: Let’s talk specifically about the Casino de Kubasoy Festival. How did it come about? What inspired this event? What has been the reception? What do you hope people take away from this event?

HFM: The Casino de Kubasoy was created in the first year of the company’s establishment. Even during COVID, it was held digitally.

It’s an event that gives every Cuban who wants to learn how to dance casino the opportunity to do so in one week. This will be the tenth edition, counting the digital years due to COVID. The only general expectation is that everyone who comes leaves satisfied based on what they are looking for: to learn and get to know how to dance casino.

I know that the event was planned based on the Cuban perspective. That said, is the event open to foreigners?

HFM: Non-Cubans are not denied participation, but in general, we haven’t had much participation from them. It has been very sporadic.

I would like if a foreigner comes, that they do so as a school. Otherwise, it would just become one more of the same. I don’t want to compete with the festivals that already exist. I want to maintain authenticity. The moment I allow foreigners in, the event will take on a different tone. It would be more of the same. But a representative delegation from a dance school would be fine.

DLD: That’s why I’m asking you these questions. I’m aware of the irony of discussing this online, where non-Cubans can read it and be interested in attending an event that is specifically for Cubans (rather than those that are held in Cuba for tourists). Suddenly, it could be filled with foreigners, and that’s not the point.

So it’s good that you’re being clear about this aspect. This way, people know the parameters, what the Cuban creator expects, and that they should respect those parameters.

HFM: When you go to an international festival, the teachers generally don’t teach you how to dance. Practically, what they do is show you dance routines. At Casino de Kubasoy, the focus is on teaching those who know nothing.

But besides that, if I focus on foreigners, where does that leave the Cubans?

DLD: We come back to the same point.

HFM: How would I like it to happen? Again: schools come. Because then there would be a meeting between academies, which would be something a bit different. In fact, if these academies come with their prepared shows, they could be part of the evening’s entertainment.

Another thing is that we would need to adjust to Cuban schedules because the festival is for Cubans.

DLD: And that’s the good thing. You’re not compromising in that aspect. The norm is the opposite: that Cubans adjust to what foreigners want. But here, in this festival, the dynamic is different. It’s an event that empowers the Cuban.

HFM: If I didn’t do it this way, I wouldn’t have done it a long time ago. I fund all this myself, with my money. The company itself doesn’t have a financial backing. It consists of young people who believe in my dream. They don’t receive a salary. Many of them work or study, and after doing those things, they come to the company to rehearse. Everything is in line with a dream, Herson’s dream.

If I focused on money, I would have stopped doing this for Cubans a long time ago. Or I wouldn’t do the festival at all.

DLD: I understand you because that’s precisely what I do. My space, that blog I’ve had for ten years, doesn’t earn me a dime. Occasionally, someone donates something to me, but it’s practically insignificant. What I’m getting at is that I don’t live off this. I am a Spanish language teacher in the U.S. That’s how I make a living. I’m a social dancer, a casinero, but I don’t earn a living doing this. This allows me to approach this differently. That’s why I feel so connected talking to you: we are both doing this because we care about our culture, improving what exists, revitalizing the tradition, and empowering Cubans.

Tell me about the most challenging aspects of trying to create spaces for Cubans to dance casino.

HFM: First, the current circumstances. There is a lot of interest in reggaeton and other genres. These genres have taken over. Second, the economic situation. Everything is getting more expensive. Before, you could buy a beer, but now you can’t. The transportation situation is worse now, too. Between transport, entry fees, and something to drink, if a regular Cuban goes to a place to dance casino, they can’t go anywhere else that month—or they have to come up with ways to make ends meet. Between buying food and going out to dance… I think the choice is pretty clear.

DLD: Why is it important for Cubans to learn how to dance casino?

HFM: Because it’s our culture. Cubans are famous in the world mainly for our culture—a culture that today is exploited through events and schools. And it’s sad how, in Cuba, there are very few opportunities for Cubans. We know that those who manage to enter art schools do so because of their talents or certain things that happen in our country, and truly, not everyone has access to that.

I believe that what makes us who we are is our culture. The casino dance has been the most popular dance that has managed to resonate with all Cubans. People still dance son and rumba, but even the sonero and the rumbero dance casino. It has been the pinnacle of our popular dances. It’s something that defines you as a Cuban. In fact, the perception of us in the world is that everyone knows how to dance casino, which is not true.

I consider the work I do to be necessary—it’s essential for me—because we are getting worse every day. When you ask the new generations what the national dance of Cuba is, the answer is anything but danzón.

It really is a complex and arduous task. Besides the economic conditions in our country, it is now more challenging for young people to want to learn. It’s incredibly difficult for us. It’s not something that’s easy to do. But we believe in what we want to achieve.

This goes beyond politics and parties. Governments come and go.

And as Enrique Pinti said, “Only the artists remain.”

Notes:

- Click here to learn more about escuelas al campo. ↩︎

- “La Lenin” is the Vladimir Ilich Lenin Vocational School, a pre-university educational institution and one of the most prestigious in the country. More information about the school by clicking here. ↩︎

- I have written extensively about this. Click here for the article. ↩︎

- Click here to learn more information about this amazing, nation-wide cultural iniciative. ↩︎

About Herson Fernández Machado

From a young age I have been involved in artistic activities in the community and participated in many dance events organized by the community. During primary school I took various classes in Cuban folklore and traditional dances.

In July 2008 I graduated from UCI university as an IT Engineer. During my studies I participated in performing arts activities through national university groups such as INFODANZ. With these groups, I won various prizes at different levels both as dancer and director of the university’s Conjunto Folklórico Universitario Ilú Ashé. As director and dancer for this first group of mine, I participated in numerous projects. After I finished my social service, I left university and joined a school for Cuban dances, Viadanza, from January 2011 to November 2014. During that time I also worked on various assignments for the company Danza Chévere.

When I finished my second year of social service I became a dancer for the group Espectáculo Villa de San Cristóbal. During the next 6 months I became its producer for 4 months and then assistant director. At the same time I started setting up a children’s community project named Manantial, where I teach children basic dance and theater. Currently, I am establishing and consolidating my new dance company, Kubasoy. In addition to being the general director, I am also a dancer and instructor for Cuban dances for the company.