While this blog has focused mainly on the dance of casino, at times I have had the need to write posts pertaining to Afro-Cuban secular dances such as rumba, as well as religious ones. I have done this because for more than a decade, there has been a trend (mostly outside of Cuba) to mix Afro-Cuban dances with the dance of casino. I have written at length here about why I do not mix the religious dances of the Orishas when I dance casino. I have also written here about when it is musically appropriate to do rumba guaguancó when dancing casino. These are by no means concluded topics, as they are currently hotly contested online, such as in this short video created by Cuban artist Alfredo García; or this Instagram reel from renowned Cuban rumbera, Ismaray Aspirina.1

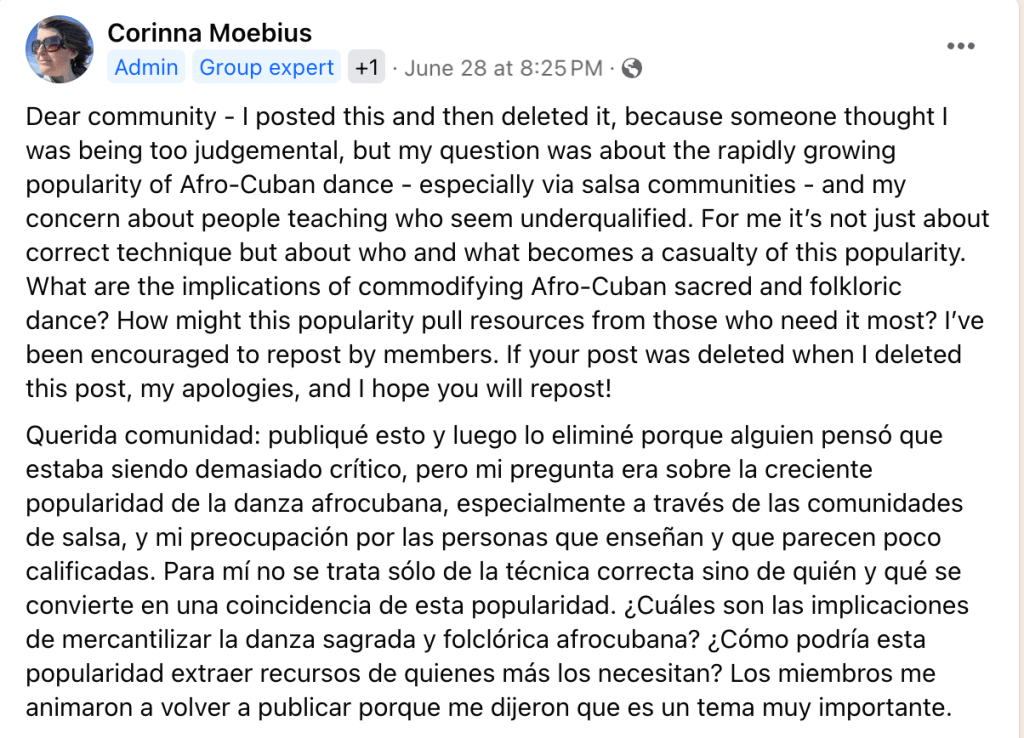

For years, Afro-Cuban dances have been carelessly commodified not only in the Cuban dance community, but also in the salsa community.2 These dances have often been taught in very decontextualized ways, and many a time as add-ons to the “main dance” (be it casino or salsa). I am not going to go into the why here because I have already given my takes on this article and this article. What is important to highlight from this phenomenon is that the ways in which these Afro-Cuban dances are commodified for consumption give rise to a number of ethical issues that I think are very well summed up by the following post:

When I read this, I knew I had to talk to Corinna. Not only was she a fellow academic, but I had been also working on a similar topic in relation to casino (we’ll see when I can finish that post). I figured I would talk to Corinna because it could be fruitful to explore the ways in which our work intersect, precisely to underscore the fact that this is part of a bigger, systemic problem that we all should be paying attention to.

Now, some of you might be wondering why I took the time to talk to a white woman about ethical issues pertaining to Afro-Cuban dances. Why am I not talking to black Cubans? The reasons will, I hope, become clearer as you read the transcript of our conversation.

As a student of Afro-Cuban dances, Corinna conducts herself with self-awareness, solidarity, empathy, courage, and gratitude. You will see these traits pour forth seamlessly and genuinely through her words.

You will also see−and this is the most important thing for me as a Cuban−what it truly means to be an ally.

DL: Tell me about who you are and how you came into contact with the Afro-Cuban dance community?

CM: My name is Corinna Moebius. It all began around 2000 in Washington, D.C. My boyfriend at the time was a really talented conguero3 (not Cuban, but Latino). He had met Marietta Ulacia, who is Afro-Cuban and who had co-founded and was directing a non-profit called The Latin American Folk Institute in Mount Rainier, Maryland. Her primary background is in music, but she was teaching Afro-Cuban dance classes. She kept telling my boyfriend, “You’ve got to get your girlfriend to my Afro-Cuban dance class.” I kept putting it off until they had a fundraiser. I won one of the prizes: a free Afro-Cuban dance class.

From Day 1, I was hooked. And it wasn’t just the class, but the community that was there. It was drawing a lot of Cubans and boricuas to hang out as a community, including congueros and batá drummers. I just loved it. During that time, I was also meeting people in the santería community (Regla de Ochá, Lukumí).

So I was learning about the Cuban community through music and dance. Later, I was briefly part of the Afro-Cuban dance company that Marietta founded: Ashé Moyubbá. They had visiting artists from Miami, like Ezequiel Torres, Oscar Rousseaux Pons (Oscar actually ended up moving to the DC area, and he became the new teacher of the classes). I also began attending every year the IFE-ILE Afro Cuban dance festival, organized by Neri Torres (Ezequiel’s sister) and later wrote a grant for the festival (see interview with Neri). I got really involved with Marietta’s non-profit. She herself was like a mentor to me. I learned a lot from her personal stories and experiences. I volunteered at the institute and eventually became a board member.

I moved to Miami in 2006. Through Neri, I had a connection with a board member of Viernes Culturales, the monthly arts and culture festival in the heart of Little Havana. My first job in Miami was directing the festival.

What started in D.C. as a random act of luck via a raffle ticket turned into my passion. After I arrived in Miami, it only deepened. I wanted to know more about Cuban history and culture–every aspect that I could. And in Miami, I was really able to be in contact with a larger number of Cubans in the diaspora.

DL: You are a researcher. You have a PhD. Can you tell us about your dissertation? What is the biggest takeaway from your research?

CM: I have an interdisciplinary degree. It’s a PhD. in Global and Sociocultural Studies. One reason I chose Florida International University (FIU) for that degree is because it brings together cultural anthropology, cultural geography, and sociology. And it’s also in Miami. At FIU, I was also able to get Graduate Certificates in Afro-Latin American Studies and African and African Diaspora Studies. During my time at FIU, I also received a graduate fellowship with the Cuban Heritage Collection, which is the largest collection of Cuban diaspora materials in the world.

My research was focused on racial politics of placemaking of the main Calle Ocho district (in what used to be called “The Latin Quarter”) of Little Havana. One of the things that intrigued me was the appropriation of famous figures like Antonio Maceo and Celia Cruz in this landscape, very real exclusion and discrimination in terms of housing, racial profiling, and police brutality that was very salient in the 1980s, especially following the Mariel Boatlift, and continuing to this day.

So here you have this monument of Antonio Maceo in Cuban Memorial Park, but is it really honoring Maceo’s contributions–Maceo himself? And when I started questioning how a landscape can both include and exclude, and perpetuate the narrative of colorblindness (which you also see in Cuba itself), I started asking questions about the history behind the making of this very symbolic place–the Calle Ocho district. Here, you have so much cultural investment and walking tours that narrate a story of the Cuban diaspora that scholars call “the Cuban success story” to people all over the world. I was curious about how Afro-Cubans were treated and represented–or excluded and misrepresented–in that narrative.

I found that even though Afro-Cubans in Miami did not have much say in what monuments went into the park, they did speak through the power of their own bodies, the symbolism of presence, of occupying space in certain kinds of ways, of opening up businesses in that very same district, or holding events like “AfroCuban Miami” or the Afro-Cuban Professionals Association–choosing to do their events right there in the symbolic heartland, where the narrative was elevating this “Golden Exile” Cuban whiteness. I thought it was so powerful and inspiring. I wanted to tell a story about these dynamics that I saw happening in the district.

I noticed two different kinds of rebellion. One was the rebellion in the white Cuban community to seek racial acknowledgment from Anglos (in order to have equal status as white and exert the same powers). And on the other hand, some Afro-Cubans and their allies were questioning the existence and propagation of this racial order. They were seeking ways of coexisting in a way in which these racial hierarchies did not exist. The rumba is a beautiful metaphor for this.

So I write about all of this, and the transnational dimensions of it all. How you see similarities in what goes on in Cuba vis-a-vis Miami, although it is not the same. You can’t automatically equate one place with another.

I see the power of dance to be a means of resistance, but I also see this constant effort to commodify–just like the taking of Maceo’s memory (a black Cuban), and using it to deny continued racism.

DL: I wish more people in the U.S. would understand that race exists outside of the U.S. border. On a personal level, one of the most controversial things I say to people is that I am white. This is often met with stupefaction. The U.S. was not the only placed were the slave trade existed! The entire American continent as we experience it today is a product of colonialism, and colonialism was buttressed on race.

At any rate, the reason that I am talking to you today is because I read a post you made on your Facebook group, We Love Afro-Cuban Dance. Can you talk about what you see happening in the Afro-Cuban dance community?

CM: I created this group, not as part of my research, but as an informal way to stay connected to what Afro-Cuban teachers were doing around the world. I also wanted to help other people learn about these instructors.

Within the last year or so, I’ve started noticing people who are teaching, and doing a pretty bad job of it. (For context, I studied Afro-Cuban dance for about a decade years with Marisol Blanco.)

It just reminded me of things that I noticed even when I was living back in D.C., where people would take Afro-Cuban dance classes for a couple of years, and then they would start teaching it themselves–after two years! And I am thinking to myself, “You have the resources, you speak English, you have an amazing network, U.S. citizenship–you have so much at your disposal. And now you have extracted, in a way (like with colonial extraction). You’ve taken what you wanted, and then you leave that person with fewer students. What happens to your teacher that taught you? And how much are you actually able to share?”

When I learned from my teachers, I did not just learn movements. It was so much more: the deep meanings behind movements, the attributes associated with a particular Orisha, the details of the rumba clave; but also African and Afro-Cuban history–the ways of being and knowing–the community aspect and the support and love. It’s something you can’t put your finger on because it is an embodied wisdom; also embedded there is a pride in blackness/Africanity, respect for elders and ancestors, and especially those who have contributed to these traditions.

My deep research of these dance forms and how they are part of communities of resistance has shaped my perspective. They have had profound impact against the backdrop of colonialism, repression, and violence, like the Massacre of 1912. And now we add the desire to make money–again–now to an even global scale. We have to consider the impact of this on the people who have spent years studying these dances–or it might be even in their families, passed down for generations. All of these dynamics get shed in order to turn the dance into a commodity.

And I always want to ask, “What violence occurs so that something else happens that seems like growth–but growth for whom? Who benefits? Is it at a cost, and who is bearing the cost of this growth?”

DL: It begs the question, then: Why do you think this is happening?

CM: There is often this desire, when you have competitions (and this extends to social media), to want to be different. To tell the world that you know something that others don’t in order to add to your social value, to your “coolness factor”. It’s gives folks what we anthropologists call “cultural capital.”

But people are not interrogating their privilege–even if you are Latinx. If you’re not interrogating your racial privilege, then you’ve got some work to do. Folks are not reflecting on how they might be reproducing inequalities, even if inadvertently.

The colonial idea of whiteness on top, and the perception of blackness as primitive and exotic, still haunts us today. People have no qualms about doing these dances, but then treat the Afro-Cubans or others of African descent in their communities with disdain. I’ve seen it myself with Afro-Cuban teachers who are brought in to teach. Those who attend their classes are in awe of this one individual; meanwhile, the same people live in fear of the Black people in their community.

And the violence is real–including violence against practitioners of these traditions. For instance, I used to go to these wonderful rumbas at Top Cigars on Calle Ocho, in Little Havana. And I was there when police and code enforcement agents basically raided Top Cigars during the rumba, and during the monthly festival, Viernes Culturales, without cause. This is a common practice in Miami–the weaponization of code enforcement–especially against people of color..

There has to be a conversations about all of this–and they are happening: Afro-Latinx groups are pushing for these conversations. I just don’t think the dance community is having enough of these conversations.

DL: When you talk about these things, I think about the white rapper who uses the form and becomes popular because of his whiteness, but does not really care about black issues. So when the Breakfast Club asks Little Dicky what he is doing for black people, he calmly responds that he is not doing much because he is not a “cause-based person.” And yet he’s making money off Black culture.4

And I make this comparison to illustrate the fact that this is precisely a systemic issue that goes back to colonialism. As you say, it is important to interrogate our positionality,5 and the ways in which our identities intersect. If we do not do this, then we are bound to remain blind to how our actions might leave (Afro-)Cuban people in the very periphery of their culture.

Take, for instance, a white woman who opens up an Afro-Cuban dance academy with the money that her grandmother left her (hello, generational wealth!) in the same city as her Afro-Cuban teacher, who arrived from Cuba two years prior. Not only does she, the white woman, have more resources, which she can pour into making the studio better looking; she also has a face that, in this (post?)colonial society is deemed safer, in comparison to that of a black woman. And so a person like this, who is not thinking about her positionality and her privilege, and who is doing this as a hobby, ends up taking people away from her teacher, for whom this is a way of making a living–all the while thinking that the people who are coming to her classes are a result of her hard work–and not as a result of white supremacy.

This is why I like having these conversations with people who are in community with Cubans. What I’ve found is that people like you, Adrian, Nicole are intentionally thinking about their own positionality and how they can leverage it, not to take things from Cubans, but to put things back in the community.

CM: I want to mention that I’ve also witnessed this in the context of tourism. It is a huge industry. In Cuba, I recall seeing a dance group (performing a fusion of Afro-Cuban rhythms and percussion with flamenco dance) that was founded by an Afro-Cuban man, but most of the dancers were white or white-mestizo. A white Cuban man was interpreting for the founder, because he didn’t speak English, but he was not translating what the founder actually said. And the false information he shared about batá drums, for instance, infuriated me. I also noticed on the wall a poster of the performers who had been able to go to Florida for a performance–all of them white Cuban except for the founder. And their cultural project was in the middle of a predominantly poor, Afro-Cuban neighborhood. So this cultural project was not about serving residents of the neighborhood. It incorporated Afro-Cuban music and instruments but the money was going to white Cubans: they remained in control. This is very pervasive, and it also speaks to whom gets all this money from tourism.

There are lesser-known Afro-Cuban rumba groups that are phenomenal–that compose new rumbas and honor the tradition–but they’re not getting nearly as many opportunities to perform for tourists. They also tend to have less access to venues where they can perform or offer classes. When I have led tours in Cuba, I have gone out of my way to support the groups that are being excluded, like Descendencia Rumbera.

I also want to mention that in the “We Love Afro Cuban Dance” group, when the Black Lives Movement was becoming better known, I wrote this post:

DL: That was beautiful and very powerful. I’m interested to see what the reaction to that post was.

CM: It had 137 Likes. I received a lot of positive comments…but mostly from people of African descent.

DL: [Laughs] That’s why I said I was interested in the comments. That’s what I figured you would get.

CM: Silence.

There are a lot of folks who feel uncomfortable talking about race. It’s hard, but I think we still need to have these conversations.

And that’s one of the things that troubles me about the group. I do not want to just keep posting videos of people dancing. I think we need to have conversations, and a more historical understanding of why these dances matter. Changó represents more than Changó. These dances can represent strategies for resistance. How do these things get extracted in such a way that you still have these issues repeating. And people continue making money while these injustices exist–and this person making money…is likely as white as I am.

DL: And usually, that person does not fight against injustice, either. They perpetuate it.

CM: I also think that sometimes white people think that they are doing their job by taking the class, promoting the heck out how much they love it; promoting tourism to Cuba; becoming a sort of cultural ambassador. That’s not enough. Who are you doing it for? Are you doing it for you? To make yourself look cool? Or are you doing it to actually affect racial injustice?

DL: I completely agree. And this is not to say that you have to engage with these issues in this way if you take a class. You go to a Mexican restaurant, eat the food, and not engage in Mexican politics. But there is a difference between someone who just wants to take a class, and someone who promotes Cuban culture. The standard has to be different.

I want to actually address the questions that you posed on the Facebook post, and I want to have your answer: What are the implications of commodifying Afro-Cuban sacred and folkloric dance? Can you first explain the concept of commodification?

CM: To commodify culture to turn a cultural practice or something ordinary and commercializing it – turning it into a commodity, something that has exchange value and can be exploited in a market. People need to make a living, of course, but over time commodification can lead a cultural practice to lose a lot of the meaning it had in its cultural context–and it can become treated as a “property” that other people take over and profit from–people who are distant from this tradition and already have a great deal of privilege.

To me, culture is not a noun but a verb because in culture things are always moving and changing. Yet when you start thinking of culture as a commodity, as something that you can have and sell, that you can package, it instantly involves a cutting off of other aspects–like its history, the relationship with communities, etc.

DL: You mentioned that you studied under Marisol Blanco for many years. Can you explain what Marisol’s class was like, precisely as a way to explain how a dance class can transcend commodification? In other words, what does it look like when the dance is not being taught as a commodity?

CM: Marisol, when she teaches, depending on what is needed or how she feels (she is very responsive to what she is feeling from the students that are in class on a particular day), she can go deep into the history, rhythms, and understanding the relationship between rhythms and movements; understanding the embodied meaning of what you’re doing; bringing it into historical context; giving it a time-space connection. When you are in her class, you feel this sort of sense of a knowledge that is flowing, that is connected to other places and times.

But it’s not just that. For example, I recall sometimes seeing women, especially of African descent, coming to her after class and expressing this deep gratitude, as if they had finally found a space of healing, of support, of welcome, of being seen, of belonging. I have interviewed some people who took her classes. One woman told me that she had found the warrior within her, even though she is known as a very kind person, but she needed to tap into the warrior part of herself. It wasn’t on a superficial level, but rather on a very profound one because of the passion with which Marisol teaches. This is part of her lived experience, of her religious positionality as a santera, a daughter of Changó. It’s part of her survival here, as an Afro-Cuban woman. You get a sense of all these linkages, these connections.

It wasn’t “just another class.” You can’t market that. You cannot commodify something that is so deep and richly embedded.

DL: This is so amazing to hear, and it stands in such stark comparison to these ready-made products, these six-week courses that promise to make you “great” at whatever dance. And it also illustrates what people (who do not even come close to having the lived experiences Marisol has) take away from the community at large when they decide that they want to teach in the same city as their (Afro-)Cuban teachers.

OK. Now that people understand the concept of commodification, let’s go back to the original question that you asked: What are the implications of commodifying Afro-Cuban sacred and folkloric dance?

CM: Afro-Cuban religions (some people say “African-inspired Cuban religions”, others say “ethno-religious traditions”) began initiating whites as a strategy of survival. By bringing outsiders into Palo, Lukumí–even into Abakuá, for instance, Afro-Cubans built a network of connections with people who had access to resources, who could give you a connection that could bring you safety or health. That was helpful to bring into your godparent relationship because when you have a godchild in these traditions, that godchild is supposed to look out for their religious elders. So a white Cuban initiate could be helping to support their Afro-Cuban godparent in the religion.

When you are teaching Afro-Cuban dance, I think of something similar. You have this opportunity to learn the tradition. But what are you offering in return, beyond just the money for a class? Where is the reciprocity? For example, have you gone on to teach others without the blessing of the person who taught you. What does that say?

Part of the implication, then, of this commodification is the breaking of this student-teacher relationship that is supposed to create a lineage, this continuous flow. You’re breaking the branch. And also…you’re being very colonial when you do it. You’re basically doing colonialism 2.0. You are extracting something for your benefit and potential profit, but you’re not thinking about where that comes from, if you’re not thinking about that reciprocity and what you’re doing to support the cultural context and what you’re doing to address racial inequities. And it’s not just about supporting your teacher, but reflecting on the larger meaning of these traditions–how they grew as practices of resistance–and resistance against what? Against anti-blackness that continues to this day.

You don’t have to be out there on the picket line. It doesn’t have to be this big, dramatic thing. But on the most basic level, what are you doing for your teacher? How are you helping your teacher get opportunities? And are you doing the work to interrogate your privilege –and better understand the systems and the structures of white supremacy?

Something that I will give myself credit for is that I was the person who helped Marisol get started. I advertised the heck out of her classes, recruited people, found her gigs, and I kept connecting and introducing her to people. That’s what you do: you show gratitude. You show love.

DL: You’re also leveraging your privilege, which is what allies are supposed to do.6

CM: Absolutely! And to me, that’s the spirit of Elegguá. That’s the trickster aspect. You can be in a society that still operates with white supremacy, but you can keep pushing back against it, you can challenge or disrupt it. You can do all sorts of creative things to disrupt this binary that white supremacy depends on. You can also do lots of things that can bring healing and connection and interracial solidarity and support.

There is a responsibility to be doing this kind of dialogue and reflection. Here is one thing that can be done. Very practical. Let’s say that you’re bringing a person to your dance studio. Don’t just have them teach the class. Create a time for a Q&A, where you’re listening and translating, and you’re helping this individual be recognized as a whole human being. Give them the space and time to share their story, in their own words, about what they’re going through, what their journey or their elders’ journeys were like. Let dance be a vehicle for education that is whole.

One of the dynamics of white supremacy, too, is always reproducing this binary in which all that is “global blackness” becomes the body, and just the body – not the mind. Just a working body. The body for white pleasure. Let’s disrupt that dynamic. That dynamic gets reproduced when it’s “just a class” or “just a performance”. The person doesn’t get a chance to speak, they are not given a space to tell their story beyond the teaching of the dance form.

DL: I would add that you can replicate these dynamics regardless of race precisely because we live with the remnants of colonialism, which in turn makes us internalize that oppression. Of course, a white person is way more likely to go on their own without their teacher’s blessing, but I’ve seen black people do it, too. It’s about recognizing how these systems of power affect everybody.

CM: I study and research what is known as “global white supremacy.” In it, there is the concept of “global whiteness”,and you can receive privileges of global whiteness without being white.

If you know how colonialism operates (and you can educate yourself about that), then you can learn how to be subversive to it, how to resist it, how to disrupt it. I know it’s very big, and very systemic; but in your own small, humble way, you can still do something instead of just being (sometimes without realizing or intending it) cogs in a wheel.

DL: This is why being in community is so important. Because then you don’t see this person as just a “dance teacher.” This is a full human being with a whole range of emotions–and even sometimes contradicting ideology that you might not like–but that’s precisely what being human is all about.

What I see in these congresses is that there is very little interaction with the instructor beyond the workshops. What is important is what they can do with their bodies. It completely dehumanizes the person.

That’s why in Cubason, an event that I am helping organize, we are going to do panels. One of these panels will feature an all Cuban cast, and we are going to talk about how we feel about what’s happening to our social and religious dances abroad.

At any rate. Let’s get to the second question you asked on the Facebook post: How might this popularity pull resources from those who need it most?

CM: My heart breaks sometimes when I think about the many talented Afro-Cuban musicians and dancers that I’ve met over the years, whether in the U.S. or Cuba. People who were living in really precarious conditions, and yet were honoring their ancestors; it permeated every aspect of their lives. But they were not receiving the recognition, the opportunities. Despite their talent, they had to struggle so much harder to forge their path. In fact, when a sonero that I know (Julio César Rodriguez Delet) moved to Miami, other white soneros did not want to give him an opportunity. His father wrote “Son a la Casa de la trova”–that’s his lineage. He’s now doing really well, thankfully. But I witnessed the jealousy.

I think about the number of times that I’ve met well-meaning people, white or African-American, for instance, who relatively quickly started teaching these forms without doing that interrogation about the fact that this was the one source of income for their Afro-Cuban teacher. When you speak limited English, in an English-speaking context, your job options are limited!

You need to interrogate your economic and resource privilege. It might seem fun and innocuous. But realize what for you might just be a hobby and an extra source of income on top of savings that you have, well, you might already have a network of contacts and friends that are supportive to you–in other words, social capital. You might have class, race and citizenship privilege that opens doors for you–and it can lead you to inadvertently “squash the competition.” Your opportunity can end up having disastrous effects for the people who need it most, who need this income to eat, to live, to pay rent, to take care of basic expenses.

These things are hard for me to swallow, in terms of empathy and ethics.

DL: I mean, you’re the living example of this. You’ve taken classes for 15 years, and you have not ever thought about teaching.

CM: Even if I were a professional dancer, I don’t even think I’d be ready, or that it would be appropriate for me to teach. When I think about the nuances that Marisol has taught us, trying to remember all of that and then pass it on…no. I wouldn’t be able to teach that to my students. I have other gifts to give to the world.

Now, there are communities where there is no Cuban teacher. But if you are living in a community where there are other Afro-Cuban teachers available, let them have opportunities! Do everything that you can to help channel some resources, opportunities, and visibility to this person. And even if you are asked to teach, you say “No.”

There are opportunities where you can be the vehicle for transformation that gets people to the Afro-Cuban teacher; you can have that role as the connecting person, but you do not have to be the replacement. You can help organize the class, or bring in resources. And it’s also important to have the humility to realize you’re not ready and to not pressure your teacher to give you the blessing. I know Marisol has really given her blessing to certain people, and I’ve noticed one thing: they are always giving her credit. They understand they are part of a lineage. It isn’t just about them.

DL: This is not a question that I was going to ask you originally, but based on what you are saying, now I am curious. One of the things I often hear people say when they create their dance groups–in spite of knowing very little of the dance–is that there are no Cubans in their community, and so in the absence of them, who else would do it? For this hypothetical non-Cuban person, (Afro-)Cuban dancing has become a way to channel something in their lives that they absolutely need; and so they feel the need to create the space for it.

So let’s do a hypothetical. Let’s say you, Corinna, move to the middle of Iowa (just to name a state). There are no Cubans in this community. Would you say, “I miss Afro-Cuban dancing so much. Let me open an academy and teach these dances.” Would that be something you would do?

CM: No. This is what I would do. Let’s say that I had a non-profit that had a dance space available. I would get together some grant money (or something along those lines), and create an event where I would bring some amazing teachers. Maybe through these opportunities, I bring some people who might be looking to relocate because they are living in a “crowded pond,” competing with other Afro-Cuban dance teachers. That’s what happened with Oscar Rousseaux. Marietta was there, but she was directing the nonprofit, and doing a great job at it!. Oscar came to DC and saw an amazing opportunity there, and he stayed. He continues to contribute to the Afro-Cuban dance/music and religious community in the DC/Maryland area.

For Afro-Cuban teachers, it is important to be able to find a community where there they can have enough students…so that they can then survive, teach and grow a business, as an entrepreneur. We have to give credit and look at teachers as entrepreneurs, as business owners. How can we support their success?

So, how can I facilitate giving someone an opportunity where, if there is enough interest generated by this event, and the person likes the community and feels appreciated, that they move to that place and settle down there. There are communities where exactly this has happened.

Like that’s what happened with Marisol. Neri Torres had been teaching in Miami, but she was off to graduate school in Boulder, Colorado. Marisol was new in town, and she was looking to teach, but studio owners didn’t think there was enough interest. But there was interest! A friend of mine and fellow Afro-Cuban dance aficionado encouraged the owner of a studio to hire Marisol. And like I mentioned before, we began promoting the classes. I helped create a website for Marisol, and postcards to promote her classes. We got her on social media. And because she’s a great teacher, her classes began to grow. We spread the word about her to local institutions, and they began to recruit her to teach and perform, too. Now she’s performing and teaching around the world!

And Oscar came to DC as a part of a workshop sponsored by the Latin American Folk Institute. And the students loved his class so much, and he was so welcomed by everyone, he decided to stay. Now he’s also a batá drummer and he’s doing quite well living in Maryland with his wife and child.

DL: What I am hearing in your answer is that, at the end of the day, to be able to do what you propose, it requires you to think about your position and cede that space, to put the people of the culture first.

CM: It does. Another example of this is what I see in Little Havana. There, Cuban culture equals a cigar, a mojito, a salsa dance class, a cafecito. Marketers “sell” Cuban culture as a bunch of “things.” People ask me, “Where do you get the best cafecito?”–and to me, the question is ridiculous, because it’s not about the taste of a tiny cup of Cuban coffee. It’s about the conversation you have with the person who makes it and with the others hanging out at the ventanita. I send them to Guillermina at Los Pinareños, who makes a fantastic cafecito, but also has a conversation with you. She’s known as the abuela of Calle Ocho. IYou get to know the human being behind who is making your coffee.

With Cuban culture, there is this romanticism of what Cuba once was. People want to consume that idea. And there is a lot of interesting writing that talks about this idea of “eating” this exotic blackness, of eating the other – which is something black feminist scholars bell hooks and Saidiya Hartman write about.

Sometimes I’ll hear white folks say that they don’t have a culture, or their culture is “boring”. Especially within a white supremacist system, there is this idea of whiteness as being bland, and textual, and apart from the body, and so people want to experience a sense of rebelliousness by taking classes that have “vibrant movements”. It’s so fascinating to me how these tropes continue through history.

DL: I would argue that the perception of white culture as “bland” is precisely on purpose, so that it doesn’t have anything that can be “attacked”, and thus preserve white supremacy.

CM: Absolutely.. And it was part of the World Fairs that were popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These fairs propagated the idea that you understood your whiteness in relation to spectacles from the such-and-such culture or tribe. So you construct your own identity–your whiteness– in relation to a performance by an othered group. To me, that continues to this day.

DL: That is such an interesting take on the world fairs. I had never thought of that.

A couple more questions before we end. Your post specifically talks about what is happening with Afro-Cuban dances in the salsa scene, which is separate from the Cuban dance scene. Now, I know that the same thing that you criticize here is happening in the Cuban dance community as well. Many a time, the Cubans themselves are teaching these dances as a commodity. I’d argue, in fact, that what you see in the salsa community is a ramification of what is being done in the Cuban dance community. I feel that the salsa community feels empowered to do this because the Cubans themselves are doing it. In other words, non-Cubans are replicating what Cubans are already doing, which in turns acts as a sort of validation for when it’s done outside of this community. The question is, what is the contextual difference between a Cuban who does this, and a non-Cuban who does the same thing?

CM: I would also add that this happens in the religious community, in Santería, for instance, but this was pushed through efforts of the Cuban government to promote tourism through “folklore.”.

That said, when Cubans self-commodify their own culture, it’s seen as a way to survive. And, in certain ways–it can serve as a means of resistance–and I would read the work of Aisha Beliso-De Jesús to read more about that. I do think that people watch what other people do and ask themselves, “What do I have? What can I sell?” In the competitive landscape, they realize that they can leverage the caché factor, as a way to sell a good that has an extra “something”, that is unique, that people want to consume. And if that brings more money, so be it. But I do not think that people are always realizing the long-term implications of selling cultural forms as a commodity.

DL: (Or even have the framework with which to understand these implications.)

CM: Absolutely. In my own experience in Little Havana, for example, at first I was the only tour guide and was actively trying to push back against characterizations of Little Havana that were racist, actually. At the time, it was considered a sort of ghetto, a slum.

But then, as more tour guides began working there, the big companies came in. They had done this before. They had the resources and marketing power we locals did not have. They hired guides for very little money, and the businesses that could afford to would give them commissions. And their guides repeated a single story. We local folks were pushed to the side. Now you see the souvenir shops, the chain stores. The neighborhood transformed. If we were better prepared, we would have known about these tactics in the global tourism industry–which in many ways perpetuates colonial narratives and practices.

You think you’re being an ambassador, you think it’s good that you’re making money. But you don’t understand how the “big dogs” who have been doing this for a while–the people at the top of the food chain in the events and tourism industry–tend to look for the hungry people. When they see that you’re hungry, they will use you, they will get everything they can from you, and then they will set you aside. And I’ve witnessed this myself. It has happened historically. It is well documented, as this happens all over the world. (see this article, for instance, and this article)

The short-term gratification of selling something might feel good–and bring in much-needed income. But without understanding the systemic ways in which you don’t have the same kinds of resources, access, networks that these other folks do. And they will leave you in the dust, and people will forget. You have to be really careful and ask yourself, “Am I creating a commodity?” Because if it is, then it is a lot easier for a bigger entity to sell it and claim it as their own. But when you’re letting people know that the only way to truly understand is in community, then you are protecting it.

Highlight your background, what is unique about you. Highlight what your class offers in terms of community-building and relationships. Build relationships with others in the community. In other words, offer something that these big entities cannot offer. If you’re going to dance at a festival, make sure there is time for people to hear you speak. Talk about your lineage in dance. What I’m saying is, make the relationships you are a part of visible, because commodification depends on you erasing them.

My whole thing is that you cannot take things out of their contexts–or rather, you can say that you are, but it’s changed the moment you remove it from its context. You have to understand the cultural community, the relationship among different cultural forms. And that to me requires literally a fundamentally different way of looking at yourself and the world. The way I look at the world, in a de-colonial kind of way, is as a web of life. A I recognize that I live in a world where we live with the effects of ordering and domination and exploitation–and that some have to endure these effects far more than others. But I interrogate this ordering, I confront white supremacy, even though I’m implicated in it and I am privileged because of it. I see all these relationships, be it human or non-human, these connections, these reciprocities, and these networks of caring. It sustains me to recognize that I exist in and as part of the web of life, the Living Earth. And dancing reminds us of that web of life, if we let it.

How do we get back to caring? One of the things about capitalism is that it gets people to thinking that life is a rat race. And what they do is they think that their liberation means doing better in the race, but they are still in the same mindset. They still think that life is inherently a rat race–a competition. That’s their frame. Every time they think they are doing better, they will get pushed down because someone is profiting from their work. It’s like a pyramid scheme. You can subvert that by changing your frame. You can think about yourself in a a different, more transformative way, and this is what the philosophical and metaphysical teachings of these cultural forms help us learn and recognize.

DL: This leads me to the last question. We have talked about how the lack of questioning of our positionality, of the ways our identities intersect to create privilege, often leaves Cubans in the periphery of their own culture.

What are some concrete steps for being a better ally–where allyship means you are in community with Cubans, you include Cubans in your projects, and you cede space when you need to?

MC: Understanding your privilege is a long journey. Bell Hooks talks about this idea of interrogating yourself. It’s not something you learn to do overnight. And it’s not just about understanding racial privilege. There is also Global North/Global South dynamics. I would recommend learning d about the history–and especially the racial history– between the U.S. and Cuba. It’s pretty fascinating and there are great books out there that can help you dig a little deeper. The histories of these two countries are intimately intertwined, and you will learn more about yourself in the process. This can be a sort of “homework assignment.”

In terms of being of allyship, it’s important to be reflective of how the world unfolds for you in ways that it might not unfold so easily for others. Of how can you step back to give others space to be welcomed. It is important to be more aware of how colonialism creates these binaries such as the one of the body vs. mind. As such, you need to help create spaces for people to be recognized as a whole human being; a space where it’s not you who is the expert, the authority. It’s important also to think about how to leverage your resources, your connections, to help someone who is from these traditions to be able to share them and pass them on.

I don’t have all the answers, but I know that there are issues that are simmering. There needs to be spaces to hear how those issues are experienced on a personal level–and also have some scholars who can speak in plain language and help people understand the systemic aspects of what is going on. Having these spaces where people can speak freely helps because it can bring up issues that maybe you, if you are a person with class, racial or Global North privilege, have not been thinking about. It can spark you to be reflective.

DL: As you mention creating spaces to have these conversations where those affected by these issues can freely express themselves, I do want to name the fact that I am talking to you, a white woman, about these issues, and not to Marisol, for instance, precisely because she cannot speak about these issues without having repercussions. We do not seem to be there yet.

CM: Yes!

DL: That’s why I am talking to you. I am totally leveraging your white privilege here. [Laughs] For me, this conversation is setting the foundation for Marisol and others, in case they ever speak publicly about these issues. Now at least people will understand the context (hopefully).

CM: As a white Anglo person, one of these privileges is this feeling of comfort. But some scholars and activists often ask, “Is peace really peace if there is no justice?” In other words, being comfortable–in your space of “peace” is your privilege, because it means you can turn away from injustice that persists. But we’re all in this world together. We’ve got to look out for each other, extend our caring! To me, it’s important to speak about race and racism, even though it has led me to be criticized over and over again. I endure it. I don’t think it should just be on the shoulders of Marisol or other people of color to bring up these issues. White folks can help normalize these conversations. We have to have the courage to feel discomfort and to take the heat. Versus reproducing the scenario of the angry black person: “Look at them. They are the problem. They are the ones who are bringing it up.”

DL: This makes me think of the comment, “Why are you so hung up on slavery? It ended hundreds of years ago”.

CM: Indeed. This is a collective effort, and it is in the best interest of everybody to have these conversations. The colonial matrix of power, as it has been called, is repressive to everybody, and it continues here, now, and globally.The brunt of the violence goes on the shoulders of those who are in that category of “global blackness”, but that does not mean that that white supremacy is not oppressive to the whole and the ways in which we operate in the world. Indeed, it is oppressive to our entire planet.

If you’re learning the dances of Elegguá, think about what he teaches us about the power of the trickster. The trickster can disrupt binaries, that’s why his number is three, not two. Elegguá pushes us to learn to deal with what makes us uncomfortable. To learn from being in the crossroads. To make wise choices. And so, Elegguá invites us to subvert our privilege and frustrate the continuities of colonialism. We can choose to be in community with Cubans and not become another version of Columbus. . Being in community is very powerful. And healing.

Notes:

- I recently participated in a panel discussion with renowned casinero Yanek Revilla in which he also criticized these fusions of Afro-Cuban dances with casino. You can watch the entire panel here. For this particular topic, start watching from minute 32:45. ↩︎

- By “salsa community” I mean linear salsa; that is, salsa on1 or on2. The dance of casino is not a style of salsa, as I have explained here. Hence the differentiation between the Cuban dance community and the “salsa community”. ↩︎

- A conguero is someone who plays the conga drums, also known as tumbadoras. ↩︎

- Video essayist, F.D. Signifier has a great video about this topic. I recommend watching the entire video. For the particular example I cited, go to timestamp 49:15. ↩︎

- As defined by Linda Alcoff in her article “Cultural Feminism Versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory”: “positionality refers to where one is located in relation to their various social identities (gender, race, class, ethnicity, ability, geographical location etc.); the combination of these identities and their intersections shape how we understand and engage with the world, including our knowledges, perspectives, and teaching practices. As individuals…we occupy multiple identities that are fluid and dialogical in nature, contextually situated, and continuously amended and reproduced.” ↩︎

- Here is a helpful video to get you started on the topic of allyship. ↩︎

ABOUT CORINNA MOEBIUS

Corinna J. Moebius, Ph.D. is an artist-educator-consultant and Founder and Principal of TerraViva Journeys. She guides people towards transformative relationships with place, community, and their bodies/selves. For decades, Corinna has advised cities and nonprofits on regenerative, inclusive and creative placemaking and civic engagement processes, earning praise from diverse community stakeholders. She has led conferences on inclusive placemaking for grassroots leaders and is profiled in an urban planning textbook. As an organizer and performer of arts in public spaces, Corinna creates place rituals that foster community connection and environmental stewardship. She has facilitated numerous community dialogues.

Corinna is co-author of A History of Little Havana (The History Press, 2015), the most comprehensive book on this storied neighborhood. Her walking tours promote nuanced understandings of culture, power, identity and place and challenge stereotypes. Corinna was featured in a PBS mini-documentary for her place-related work and has also been recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. She holds a Ph.D. in Global & Sociocultural Studies (cultural anthropology) and her research focuses on urban, public and place-based rituals of identity, race and power. She recently served as Visiting Faculty for an acclaimed urban studies study abroad program, sharing diverse perspectives on global cities through a social-spatial justice lens.

Corinna’s recommended bibliography for further research into these topics:

AfroCuba: An Anthology of Cuban Writing on Race, Politics and Culture by Jean Stubbs (Editor), Pedro Peréz Sarduy (Editor)

Afro-Cuban Voices: On Race and Identity in Contemporary Cuba by Pedro Perez Sarduy and Jean Stubbs

Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution (Envisioning Cuba) Envisioning Cuba by Devyn Spence Benson

Between Race and Empire: African-Americans and Cubans before the Cuban Revolution by Lisa Brand

Black Cuban, Black American: A Memoir by Evilio Grillo Cuba: An American History by Ada Ferrer

Cuban Color in Tourism and La Lucha: An Ethnography of Racial Meaning By Kaifa Roland

Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomble, by Yvonne Daniel

Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African-Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow by Frank Andre Guridy

Geographies of Cubanidad: Place, Race and Musical Performance in Contemporary Cuba by Rebecca M. Bodenheimer

Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation and Revolution, 1868-1898 by Ada Ferrer

Our Rightful Share: The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912 The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912 by Aline Helg

Performing Afro-Cuba: Image, Voice, Spectacle in the Making of Race and History by Kristina Wirtz

Race and Politics in Cuba By Aline Helg Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth Century Cuba by Alejandro de la Fuente

Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance: Performing the Entangled Histories of Cuba and West Africa by Jill Flanders Crosby and JT Torres

Very interesting and thought-provoking discussion!

Thank you for faithfully reading the blog!

Funny that you mention that: Yanek was conducting one of the few “inject afrocuban folklore into casino no matter what music is playing” workshops I’ve ever visited 🙂 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ux87RQDEwo

(TW: YM in the comments)

Hi dear Sonycasino (I don’t know if I should use your name), I’ve been binge-reading your website for a couple of weeks now and I first wanted to tell you how grateful I am for your work! It started with me trying to find informations on the casino dance, since starting what I first thought was “Cuban salsa” initiated a huge passion for what I found later on was really Casino, and therefore everything surrounding it (blame it on my neurodivergency or an intense personality in general, but I can’t just do something moderately and when I am interested about a subject I start making links which make want to dig even deeper).

You then became one of my main sources of knowledge about its history, power dynamics, structure and such. I’ve always wanted to express you gratitude for all the free work you’ve been doing, spreading knowledge without any financial benefits. As you’ve said somewhere else, you’re teaching things people would pay a lot to have even a small percentage of during workshops. Seeing I don’t have much money, I can only be immensely grateful for that! When I’ll be a bit more stable economically I will for sure wire some money as I think I owe you a lot in my progress.

I also love the fact that you don’t mind expressing “polemic” statements, and going against the dominant thought in dance social circles. It reminded me of those years I spent in my university, debating about political and philosophical ideas (more than studying sometimes, unfortunately), often being the only one defending unpopular ideas in my own social circles. Dancing is often seen as something outside of the realm of struggles, which it obviously isn’t as any human activities. As long as it’s well-sourced and not just a way to promote one’s ego or offensive ideology, there’s nothing more democratic than intellectual conflict.

That said, even though I have nothing to say about your opinions on Cuban culture, history and such (I am not knowledgeable enough), I have an intellectual problem with one major thing I’ve been noticing during my readings, which is very explicit here: the use of the concept of race. I am not a PHD researcher but I’ve read and written a decent amount of texts (either for political pamphlets or newspapers during my stint as a freelance journalist), and I became very interested about these (very USA-centric) debates surrounding the concept race. When I read this interview, it seemed to me you both were defending the existence and necessity of a concept such as “race”, which is where I can say I strongly disagree on both a scientifical and political point of view.

It would be too long to explain in what is already a long comment, but I really believe that, following the writings of scholars, intellectuals and militants such as Adolph Reed Jr., Cedric Johnson, Toure Reed, Walter Benn Michaels, Gérard Noirel and so on (often involved in journals such as Jacobin or Nonsite) “race” and all of its derivatives are both creations of capitalism and racism, which means that using it can only be detrimental in the struggle against both things. Most notably the Fields sisters, both Afro-American scholars (historian and anthropologist), have very well demonstrated in their essay Racecraft how “race” is a social construct, an invention of racism and a byproduct of class-exploitation, which has produced very problematic results on policies as well as studies. For example, this affirmation that “colonialism is buttressed on race” is not only something most historians would probably disagree with (colonialism preexisted race, and modern colonialism was much more a consequence of socioeconomic dynamics linked to capitalism), but it’s really actually inverting the cause and the consequence. Colonialism PRODUCED race and racism, not the opposite.

The Fields sisters talk about how race was never the issue it became later even in the USA, before European serfs and African workers/slaves started joining forces against landowners (there were even records of Africans adopting “Christian” babies). Racism and races in the USA were used by the dominant white capitalists in an effort to break what seemed to be the beginnings of proper class-struggle (unfortunately without Natives tho), as well as to justify the increasing use of slaves when Irish workers started earning more through their own struggles and therefore becoming more expensive to employ (before that, they were the large majority of the working force and their condition was as horrible as slaves later, with the exception of being legally not enslaved). The same criticisms have been made by people on different continents, marxist intellectuals mostly who saw the disaster this racial analysis was even for scientifical knowledge (it’s impossible to have a good understanding of modern history if race becomes a thing – noone can even define it or propose a set of “races”, which biologists dont use anymore). So I believe these thoughts about race are way too essentialist in my opinion.

And before anyone says anything about my own identity, I am myself of Latin-American/Slavic origins, I’ve endured racism in my youth in mostly white Belgian schools, I have no problem as an individual about talking about skin colors and such (my mom is half Latino half Native, my dad is a blue eyed Polak and it’s literally impossible to categorize me except that I look foreigner). Yet I really don’t think race exists other than in the eyes of the racist. Why then use something that, as the Fields said, is the “fingerprint that racism was there”? Race is clearly an illusion created by racism through what they call “racecraft”. Why talk to “Whites” as if they were a group? In most countries in the world outside of the USA, concepts such as “blacks and whites” are inaudible and don’t make much sense locally. Why ask them to be allies, do or not do things? This only strengthens further the structures created by racism and racecraft, instead of promoting class which can then be the foundations of a new, reinvigorated class-struggle. I struggle to see how a poor factory worker from Detroit, a jobless trailer park inhabitant on social welfare, a rich landowner from Texas and a digital worker from NY share common things and should behave in a certain way as such. Historically, “white trash” or “rednecks” were never really seen as the same as WASPS by those with power. Hell, some even argue that racism started with how the French nobles were treating and talking about the French serfs.

That said, I won’t deny I am always impressed by the ressources you put in our disposition and the powerful arguments you and your guests make. Hopefully you won’t take my comment badly, and if I didn’t say anything before it’s just because I don’t feel legitimate to talk about the subjects you address most of the time.

Thank you for reading the blog faithfully. It means a lot! I am glad it is helping you.

In regards to race. We can both acknowledge that it is a construct AND that this construct has real-life effects that currently affect people. We cannot deny race because we would be denying the disproportionate sentencing rates that black people experience in this country precisely because of this construct. We can’t pretend it’s not there, affecting the lives of millions everyday.

What we tried to do in this interview was acknowledge its existence and provide ways in which we can subvert the concept in order to make it work for—and not against.